- Articles

- Commonweal

- TIME – Reviews

- TIME – Articles

- TIME – Cover Stories

- TIME – Foreign News

- Life Magazine

- Harper’s: A Chain is as Strong as its Most Confused Link

- TIME – Religion

- New York Tribune

- TIME

- National Review

- Soviet Strategy in the Middle East

- The Coming Struggle for Outer Space

- The Left Understands the Left

- To Temporize Is Death

- Big Sister Is Watching You

- Springhead to Springhead

- Some Untimely Jottings

- RIP: Virginia Freedom

- A Reminder

- A Republican Looks At His Vote

- Some Westminster Notes

- Missiles, Brains and Mind

- The Hissiad: A Correction

- Foot in the Door

- Books

- Poetry

- Video

- About

- Disclaimer

- Case

- Articles on the Case

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1948

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1949

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1950

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1951

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1952

- Trial by Typewriter

- I Was the Witness

- The Time News Quiz

- Another Witness

- Question of Security

- Fusilier

- Publican & Pharisee

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Kudos

- Letters – June 16, 1952

- Readable

- Letters – June 23, 1952

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Nominee for Veep

- Recent and Readable

- Recent and Readable

- Democratic Nominee for President

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Fighting Quaker

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Timely Saints

- Nixon on Communism

- People

- Who’s for Whom

- 1952 Bestsellers

- Letters – December 15, 1952

- Year in Books

- Man of Bretton Woods

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1953

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1954

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1955

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1956-1957

- Private

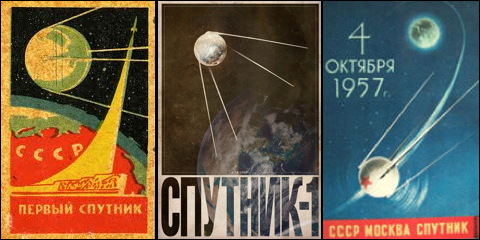

The Coming Struggle for Outer Space

The Coming Struggle for Outer Space

National Review – November 2, 1957

By Whittaker Chambers

TV utilized a break in a Braves–Yankees broadcast to amplify the first, skeptical announcement of a day or so before that Sputnik really was up there. Listening to the somewhat breathless confirmation (“it says: ‘Beep! Beep!‘”) I laughed. Neighbors, who happened to be present, asked why. I could only answer: “I find the end of the world extremely funny.” “What’s funny about that?” one asked. What could I answer: that men always defy with laughter what they can do absolutely nothing else about? Beyond that, any explanation I attempted would have been as puzzling as my reaction seemed.

I think I should have had to begin something like this. In 1923, I was sitting in a restaurant on the Kurfuerstendamm, in Berlin. What did the mark then stand at — 40 million to the dollar? The exact ratio of catastrophe is unimportant. In Germany, inflation had wiped out all small and middle bank accounts, and the value of all wages, pensions, payments, as completely and inexplicably as if the top floor of a skyscraper had collapsed and dropped the whole nation to the ground. Germany, in 1923, was a madhouse of stunned, desperate, tormented millions.

On the sidewalk beyond my table, there walked past a handsomely dressed, extremely dignified woman. It would miss something to say that she was crying. Tears were streaming down her face — tears which she made no effort to conceal, which, in flowing, did not even distort her features. She simply walked slowly past, proudly erect, unconcerned about any spectacle she made. And here is what is nightmarish: nobody paid the slightest attention to her. The catastrophe was universal. Everybody knew what she signified. Nobody had anything left over from his own disaster to notice hers.

She became one of my symbols of history in our time. About this unknown, slowly walking, weeping woman, as about certain other things, no more momentous, that were around me in those days, I came to feel at length as Karl Barth said of something else: “At that moment, I found my hand upon the rope, and the great bell of prophecy began to toll.” I began then (along with thousands of others) to draw certain conclusions about the crisis of history in this time that I can merely sketch in like this: 1) the crisis was total (in the end, none would be spared its lash); 2) its solution would fill the lifetime of my generation and the next ones; 3) the one certainty about the solution was that the stages by which it was reached must be frightful, whatever the solution itself turned out to be.

A New Dimension

Does it sound wildly irrational to say that, when the newscaster broke into the ball game, I also laughed because that woman walked again across my mind’s eye? It is so. With her began the prophecy; the circling of the scientific moon was implicit in her slow walk-past (though neither she nor I could know that). Yet to have lived with this prospect of reality for more than thirty years, and to have been unable to communicate it convincingly to others—that is the heart of loneliness for any mind. Cassandra knew.

It works out, too, in the simplest, most immediate ways. As soon as my wife and I were alone, I said: “They still do not see the point. The satellite is not the first point. The first point is the rocket that must have launched it.” Of course, the scientists and the military chiefs grasped this oblivious implication at once. But it took three or four days for anybody to say so, in my hearing.

In short, the struggle for space has been joined: But this was only the immediate, military meaning. Widen it with this datum: the satellite passed over Washington, sixty miles away. One minute later, it passed over New York. We have entered a new dimension. Like Goethe after the battle of Valmy, we can note in our journals: “From this day and from this place, begins a new epoch in the history of the world; and you can say that you were there.”

There is a wonderful passage in the Journal of the Goncourt Brothers, wonderful, in part, for its date, which cannot be later than 1896. I shall not be able to quote it exactly from memory, but it goes much like this: “We have just been at the Academy, where a scientist explained the atom to us. As we came away, we had the impression that the good God was about to say to mankind, as the usher says at four o’clock at the Louvre: ‘Closing time, gentlemen.'” None of us supposes that this moon means closing time. None of us can fail to see, either, that closing time is a distinct possibility. Again, the point is not that we do not yet have the ICBM fully developed; we will. The point is that the new weapons are, of their nature, foreclosing weapons, and, whether or not they are all presently in our hands, too, they are in the hands of others over whom we have no control. That is what I meant by “end of the world.” Only those who do not know, or who do not permit their minds to know, the annihilative power of the new weapons, will find anything excessive in the statement. “Nine H-Bombs dropped with a proper pattern of dispersal” was a figure given me, three or so years ago, as the number required to dispose of “everything East of the Mississippi River.” Whether the figure is accurate to a bomb or a square mile is indifferent. Any approximation of it speaks for itself.

Will to Inconsequence

Unlike Goethe, I doubt that any of us can feel a particular elation in being able to say: “And you were there.” I suspect that about the best we can muster will be like the historic first words said to have been uttered by the King of Greece, on landing there after the German occupation in World War II and the ruinous civil war. “Nice weather for this time of year, isn’t it?”

In those words, the end of dynastic Europe is, once for all, self-proclaimed. Their staggering inconsequence is not stupidity, but something much more final: the inability of a mind any longer to feel or know the reality which, by position, it should be shaping. Such a mind is no longer equal to the meaning of what is happening to it or to anybody else. Is not this condition growing on all of us? Is there not a deliberate will to inconsequence — a will not to know, not to see, the dimensions of what we are caught up in — a will to make ourselves, and our vision, small, in the child’s hope that, if we work hard enough at it, we can make the tremendum enclosing us as small as we are? Perhaps, if we do not look, it will go away, leaving us with the Edsel and the split-level house. How else explain the fact that, born into a century unprecedented in scale; depth and violence of disruption (the two world wars and the new energy sources are instance enough), we nevertheless manage so successfully not to know its total meaning, but to see its shock piecemeal, as a disjointed, meaninglessly recurrent hodgepodge? The attitude is fixed in a habit of minimizing complacency, commonly couched as a posture of strength. But since it does not conform to the scale of real events, it is irrational, and leads, invariably, to those equally irrational spasms of extravagant jitter or extravagant optimism (such a wave as swept the West after the Geneva Summit Conference), whose inevitable recession in the face of the facts, plunges us into deepest puzzlement.

It is a late and tired habit of mind, which we seek to glorify by twining about it the rather dry and lifeless vine-leaves called: reasonableness, the calm view, common sense, the injunction never, under any circumstances, to feel strongly about anything (which, among other things, is blighting the energy of our youth at the source). “I believe,” the little old man of twenty-one who was his college’s most brilliant political science major, explained to me, “that the tendency, nowadays, is to see everything quantitatively.” “Yes,” agreed the Fulbright fellow who was with him, neither approving nor disapproving, merely baffled, but, above all, by my extraordinary question: “Doesn’t the student mind ever get excited about anything anymore?” It is a positive will not to admit or permit greatness in event or men. But, since will itself implies a suspect energy, it takes form as a vague distaste, discomfort, distrust, relieved by a preference for the commonplace, the conforming, the small, the minutely (hence safely) measurable, the quantitative—method and dissection replacing life and imagination.

Imagination

Whatever else Sputnik is or means, the handwriting that it traces on our sky writes against that attitude the word: Challenge. It means that, for the first time, men are looking back from outside, upon those “vast edges drear and naked shingles of the world” which Arnold reached in imagination. In imagination — which is the creative beginning of everything (God Himself had first to imagine the world), the one indispensable faculty that has brought man bursting into space from that primitive point of time he shamblingly set out from. That breakthrough (all political considerations apart) touches us with a little of the chill of interstellar space, and perhaps a foreboding chill of destiny — a word too big with unchartable meanings to be anything but distasteful to our frame of mind. For it is inconceivable that what happens henceforth in, and in consequence of, space, will not also be decisive for what happens on the earth beneath. In short, Sputnik has put what was useful and effective in method and dissection once more at the service of imagination. It is the war of imagination that, first of all, we lost. It is in terms of imagination that the Russians chiefly won something. The issue has only been joined. Nothing is final yet. But it is joined in space, and it is at that cold height that henceforth we will go forward, or go nowhere. There is no turning back.

Before this illimitable prospect, humility of mind might seem the beginning of reality of mind. As starter, we might first disabuse ourselves of that comforting, but, in the end, self-defeating, notion that Russian science, or even the Communist mind in general, hangs from treetops by its tail.

(also available at National Review online)

(back to National Review page)

(back to Articles page)

(back to Home page)

One Response to The Coming Struggle for Outer Space

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Archives

Tags

Adolf Berle Alexander Ulanovsky Alger Hiss Arthur Koestler Atlas Shrugged Ayn Rand Benn Steil Cold Friday Cold War Communism Dwight Eisenhower FDR George W. Bush Ghosts on the Roof Harry Dexter White Harry Truman Hiss Case House Un-American Activities Committee HUAC Ignatz Reiss John Loomis Sherman John Maynard Keynes Joseph McCarthy Joseph Stalin Karl Marx Leon Trotsky Max Bedacht Middle East National Review Peter the Great Pumpkin Papers Ralph de Toledano Richard Nixon Ronald Reagan Sputnik TIME magazine Tony Judt Vladimir Lenin Walter Krivitsky Westminster Whittaker Chambers William F. Buckley William F. Buckley Jr. Winston Churchill YaltaArt Resources

- B&W Photos from Farm Security Administration-Office of War Information Collection

- Life of the People: Radical Impulse + Capital and Labor

- Art of Marxism

- Comrades in Art

- Graphic Witness

- Jacob Burck

- Hugo Gellert + Gellert Papers

- William Gropper

- Jan Matulka: Thomas McCormick Gallery + Global Modernist

- Esther Shemitz Chambers

- Armory Show 1913

Pages from old website

Official website of Whittaker Chambers ( >> more )

Spycraft

- China Reporting

- CIA

- CIA – Alger Hiss Case

- Cold War Files

- Cold War Studies (Harvard)

- Comintern Online

- Comintern Online – LOC

- CWIHP – Wilson Center

- David Moore – Critical Thinking and Intelligence Analysis

- DC Writers: WC Home

- Economist – Espionage

- Essays on Espionage

- FBI – Rogue DNS Checker

- House – Hearing 08/25/1948

- House – Hiss Subpoena

- InfoRapid: WC

- Max Bedacht

- New York Times – Espionage

- NSA – FOIA Request

- PBS NOVA – Secrets Lies and Atomic Spies

- Richard Sorge

- Secrecy News

- Sherman Kent – Collected Essays

- Spy Museum – SPY Blog

- Thomas Sakmyster – J Peters

- Top Secret America – Map

- UK National Archives

- Vassiliev Notebooks

- Venona Decrypts

- Washington Decoded

- Washington Post – Espionage

- Zee Maps

Libraries

- American Commissar by Sandor Voros

- American Mercury – John Land

- American Writers Museum

- Archive.org – HUAC

- Archive.org – Lazar home

- Archive.org – Lazar Report

- Archives.org: 1948 – Hearings

- Archives.org: 1950 – Sherman Lieber

- Archives.org: 1951 – Sorge

- Archives.org: Ernie Lazar FOIA

- Archives.org: Ernie Lazar FOIA Collection

- Bio – Bennet Cerf

- Bio – Zara Witkin

- Bloomsburg University: Counterattack

- Bloomsburg University: Radical Publications

- Brooklyn Eagle 1948

- Centre des Archives communistes en Belgique

- CIA FOIA WC

- Daily Worker (various)

- Daily Worker: Marxists.org

- DC – Kudos

- DC – ORCID

- DC – ResearcherID

- DC – ResearchGate

- DC – SCOPUS

- Digital Public Library of America

- Erwin Marquit – Memoir

- FBI

- FBI Vault – WC

- Google: Books – WC

- GPO – WC

- GW – ER Papers: WC

- GWU: Eleanor Roosevelt WC

- Harvard College Writing Center – WC Summary

- Hathi: WC

- IISH: Marx Engels Papers

- ILGWU archives

- Images AP

- Images Corbis

- Images Getty Time Life

- Images LOC

- INKOMKA Comintern Archives

- International Newsletter of Communist Studies (Germany)

- JJC/CUNY – HC

- Labor Archives in the United States and Canada

- Life – WC

- LOC LCCN WC

- NBC Learn K-12: Spy Trials

- New Masses (Archive.org) 1926–1933

- New Masses (Marxists.org) 1926–1933

- New Masses (USussex) 1926–1938

- NSA: FOIA requests

- Ollie Atkins Photos

- Open Library: WC

- People: WC

- Poetry: Defeat in the Village

- PSA Communism

- SLU Law: HCase

- SSRN: Berresford – Hiss Case

- SUFL: Collections

- Tamiment: Collections

- Truman Library – John S. Service

- Truman Library – Oral Histories

- Truman Library – WC

- UCBerk * eBooks

- UCBerk: China – Edgar Snow

- UCBerk: China – Grace Service

- UCBerk: China – Kataoka

- UCBerk: China – Mackinnon

- UCBerk: China – Owen Lattimore

- UCBerk: China – Stross

- UCBerk: France – Revolution

- UCBerk: Russia – Bread 1914-1921

- UCBerk: Russia – Comintern

- UCBerk: US – Conservatism WC

- UCBerk: US – Hollywood Weimar

- UCBerk: US – James Joyce

- UCBerk: US – Lawyers

- UCBerk: US – NY Intellectual

- UCBerk: US – Waterfronts

- UCLA Library Film & TV Archive

- UK National Archives: WC

- UMich: Salant Deception

- UPenn: US – Left Ephemera Collection

- UPitt: US – Harry Gannes

- USDOE

- USDoED

- USDOJ

- USDOS

- Wall St + Bolshevik Revolution – Anthony Sutton

- Wikipedia A-D

- WikiSearch WC

- WordPress themes – Anders Noren

- x FSearch – WC

[…] The Coming Struggle for Outer Space […]