- Articles

- Commonweal

- TIME – Reviews

- TIME – Articles

- TIME – Cover Stories

- TIME – Foreign News

- Life Magazine

- Harper’s: A Chain is as Strong as its Most Confused Link

- TIME – Religion

- New York Tribune

- TIME

- National Review

- Soviet Strategy in the Middle East

- The Coming Struggle for Outer Space

- The Left Understands the Left

- To Temporize Is Death

- Big Sister Is Watching You

- Springhead to Springhead

- Some Untimely Jottings

- RIP: Virginia Freedom

- A Reminder

- A Republican Looks At His Vote

- Some Westminster Notes

- Missiles, Brains and Mind

- The Hissiad: A Correction

- Foot in the Door

- Books

- Poetry

- Video

- About

- Disclaimer

- Case

- Articles on the Case

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1948

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1949

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1950

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1951

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1952

- Trial by Typewriter

- I Was the Witness

- The Time News Quiz

- Another Witness

- Question of Security

- Fusilier

- Publican & Pharisee

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Kudos

- Letters – June 16, 1952

- Readable

- Letters – June 23, 1952

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Nominee for Veep

- Recent and Readable

- Recent and Readable

- Democratic Nominee for President

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Fighting Quaker

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Timely Saints

- Nixon on Communism

- People

- Who’s for Whom

- 1952 Bestsellers

- Letters – December 15, 1952

- Year in Books

- Man of Bretton Woods

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1953

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1954

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1955

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1956-1957

- Private

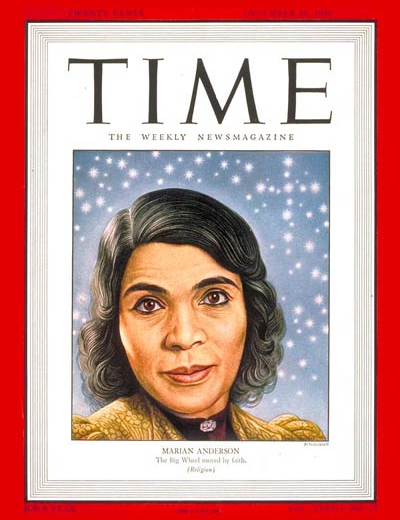

Religion: In Egypt Land (Marian Anderson)

Monday, Dec. 30, 1946

Religion: In Egypt Land

(See Cover)

Go tell it on the mountain,

Over the hills and everywheah;

Go tell it on the mountain,

That Jesus Christ is aborn.

At Salzburg, backdropped by magical mountains, where Austria’s great musical festivals were held before the war, and where he first heard Marian Anderson sing, Arturo Toscanini cried: “Yours is a voice such as one hears once in a hundred years.”

Toscanini was hailing a great artist, but that voice was more than a magnificent personal talent. It was the religious voice of a whole religious people—probably the most God-obsessed (and man-despised) people since the ancient Hebrews.

White Americans had withheld from Negro Americans practically everything but God. In return the Negroes had enriched American culture with an incomparable religious poetry and music, and its only truly great religious art—the spiritual.

This religious and esthetic achievement of Negro Americans has found profound expression in Marian Anderson. She is not only the world’s greatest contralto and one of the very great voices of all time, she is also a dedicated character, devoutly simple, calm, religious. Manifest in the tranquil architecture of her face is her constant submission to the “Spirit, that dost prefer before all temples the upright heart and pure.”

Up from Philadelphia. Thanks to the ostracism into which they are born, Negro Americans live very deeply to themselves. They look out upon, and shrewdly observe, the life around them, are rarely observed by it. They are not evasive about their lives; many are simply incapable of discussing them.

The known facts about Marian Anderson’s personal life are few. She was born (in Philadelphia) some 40 years ago (she will not tell her age). Her mother had been a schoolteacher in Virginia. Her father was a coal and ice dealer. There were two younger sisters.

When she was twelve, her father died. To keep the home together, Mrs. Anderson went to work. Miss Anderson says that the happiest moment of her life came the day that she was able to tell her mother to stop working. Later she bought her mother a two-story brick house on Philadelphia’s South Martin Street. She bought the house next door for one of her sisters.

Miss Anderson’s childhood seems to have been as untroubled as is possible to Negro Americans. In part, this was due to the circumstances of her birth, family, and natural gift. In part, it was due to the calm with which she surmounts all unpleasantness. If there were shadows, she never mentions them. Perhaps the most characteristic fact about her childhood is that Marian disliked bright colors and gay dresses as much as her sisters loved them.

Shortly after her father’s death, Marian Anderson was “converted.” Her mother is a Methodist. But Marian was converted in her father’s Union Baptist Church, largely because the late Rev. Wesley G. Parks was deeply interested in . music, loved his choirs and encouraged any outstanding singer in them. At 13, Marian was singing in the church’s adult choir. She took home the scores, and sang all the parts (soprano, alto, tenor, bass) over & over to her family until she had learned them. Since work is also a religion to her, Miss Anderson considers this one of the most important experiences of her life. She could then sing high C like a soprano.

At 15, she took her first formal music lesson. At 16, she gave her first important concert, at a Negro school in Atlanta. From then on, her life almost ceases to be personal. It is an individual achievement, but, as with every Negro, it is inseparable from the general achievement of her people. It was the congregation of the Union Baptist Church that gave Miss Anderson her start. Then a group of interested music lovers gave a concert at her church, collected about $500 to pay for training her voice under the late Philadelphia singing teacher, Giuseppe Boghetti.

In 1924, she won the New York Stadium contest (prize: the right to appear with the New York Symphony Orchestra). In 1930, she decided that she must study in Germany. When she had perfected her lieder, songs by Schubert, Brahms, Wolf, she gave her first concert on the Continent. It cost her $500 (the Germans explained that it was customary for Americans to pay ‘for their own concerts). She never paid again.

Applause followed her through Norway and Sweden. In Finland, Composer Jean Sibelius offered her coffee, but after hearing her sing, cried: “Champagne!” In Paris, her first house was “papered.” From her second concert, enthusiasts were turned away in droves. She swept through South America.

The Trouble I’ve Seen. In the U.S. the ovation continued. Only one notably ugly incident marred her triumph. In Washington, the management of Constitution Hall, owned by the Daughters of the American Revolution, announced that it would be unable to lease the hall on the date which Sol Hurok, Miss Anderson’s manager, had asked for. The refusal resulted in Eleanor Roosevelt’s resignation from the D.A.R. and an enormous ground swell of sympathy for Miss Anderson and her people. Miss Anderson, who has carefully, kept herself and her art from being” used for political purposes, said nothing.

But Washington heard her. She sang, first in the open air in front of the Lincoln Memorial. Later the D.A.R. leased her Constitution Hall, and she sang to a brilliant white and Negro audience. She had insisted only that there should be no segregation in the seating. Nobody knows the trouble that an incident like this one causes to a spirit like Marian Anderson’s. No doubt such things are in her mind when she says, with typical understatement: “Religion, the treasure of religion helps one, I think, to face the difficulties one sometimes meets.”

For this greatly gifted American, pouring out the riches of her art to houses that are sold out weeks in advance, could not for a long time travel about her country like her fellow citizens. She has given concerts in the South, where her voice is greatly admired (and where she avoids Jim Crow by traveling in drawing rooms on night trains). Even in the North, she could not until fairly recently stay at most good hotels. In the South, she must still stay with friends. In New York City, she used to leave frantically applauding audiences to sleep at the Harlem Y.W.C.A. Then Manhattan’s Hotel Algonquin, longtime rendezvous of U.S. literati, received her. Now most other Northern hotels have also opened their doors.

Usually, Miss Anderson travels with six pieces of luggage, one of which contains her electric iron (she presses her own gowns before a concert), and cooking utensils (she likes to prepare snacks for herself and she has had some unpleasant experiences with hotel dining rooms).

Agrarian Problems. In 1943 Miss Anderson married Orpheus Fisher, an architect who works in Danbury, Conn. Now they live, not far from Danbury, on a beautiful, 105-acre farm, “Marianna.” Inside, the handsome, white frame, hillside house has been remodeled by Architect Fisher. He also designed the big, good-looking studio in which Miss Anderson practices.

When not on tour or practicing, Miss Anderson dabbles in farming. She sells grade-A vegetables to the local market, regrets that Marianna, like many farms run by hired help, costs more than it brings in. And there are other problems in the agrarian life. This year, Miss Anderson was much puzzled when the big (but unbred) daughter of her registered Guernsey cow did not give milk. “Heifers have to be freshened before you can milk them,” she explains with some astonishment. “Did you know that?”

The question measures the very real distance she has traveled from the peasant roots of her people. But, as she has traveled, she has taken to new heights the best that Negro Americans are. For the Deep River of her life and theirs runs in the same religious channel. In her life, as in the spiritual, the Big Wheel moves by faith. With a naturalness impossible to most people, she says: “I do a good deal of praying.”

Gift from God. For to her, her voice is directly a gift from God, her singing a religious experience. This is true of all her singing (she is preeminently a singer of classical music). It is especially true of her singing of Negro spirituals. She does not sing many, and only those which she feels are suited to her voice or which, like Crucifixion, her favorite, move her deeply.

There are lovers of spirituals who do not care for the highly arranged versions that Miss Anderson sings, or the finished artistry with which she sings them. But if something has been lost in freshness and authenticity, much has been gained by the assimilation of these great religious songs to the body of great music. For they are the soul of the Negro people, and she has taken that soul as far as art can take it.

As the thousands who have heard her can testify, Miss Anderson’s singing of spirituals is unforgettable. She stands simply, but with impressive presence, beside the piano. She closes her eyes (she always sings with her eyes closed). Her voice pours out, soft, vast, enveloping:

They crucified my Lord,

An’ He never said a mumblin’ word;

They crucified my Lord,

An’ He never said a mumblin’ word.

Not a word, not a word, not a word.

They pierced Him in the side,

An’ He never said a mumblin’ word;

They pierced Him in the side,

An’ He never said a mumblin’ word.

Not a word, not a word, not a word.

He bowed His head an’ died,

An’ He never said a mumblin’ word;

He bowed His head an’ died,

An’ He never said a mumblin’ word.

Not a word, not a word, not a word.

Audiences who have heard Miss Anderson sing Crucifixion have sometimes been too awed to applaud. They have sensed that they are participants in an act of creation—the moment at which religion informs art, and makes it greater than itself.

Birth of the Soul. The theme of the greatest music is always the birth of the soul. Words can describe, painting can suggest, but music alone enables the listener to participate, beyond conscious thought, in this act. Beethoven’s Violin Concerto is a work secular beyond question. But when, in the first movement, the simple theme subtly changes, the mind is lifted and rent—not because the strings have zipped to another key, but by a tone of divinity conveyed through the composer’s growing deafness by an inspiration inexplicable to the mind. The spirituals are perhaps the greatest single burst of such inspiration, communicated, not through deafness, but through the darkness of minds which knew nothing of formal music and very little of the language they were singing.

Professional musicians and musicologists are still locked in hot debate about the musical origins of the spirituals and the manner of their creation. One simple fact is clear—they were created in direct answer to the Psalmist’s question: How shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land? For the land in which the slaves found themselves was strange beyond the . fact that it was foreign. It was a nocturnal land of vast, shadowy pine woods, vast fields of cotton whose endless rows converged sometimes on a solitary cabin, vast swamps reptilian and furtive—a land alive with all the elements of lonely beauty, except compassion. In this deep night of land and man, the singers saw visions; grief, like a tuning fork, gave the tone, and the Sorrow Songs were uttered.

Perhaps, in little unpainted churches or in turpentine clearings, the preacher, who soon became the pastor and social leader of his wretched people, gave the lead:

Way over yonder in the harvest field —

The flock caught the vision too:

Way up in the middle of the air,

The angel shovin’ at the chariot wheel,

Way up in the middle of the air,

O, yes, Ezekiel saw the wheel,

Way up in the middle of the air,

Ezekiel saw the wheel,

Up in the middle of the air.

The Big Wheel moved by faith,

The Little Wheel moved by the grace of God,

A wheel in a wheel,

Up in the middle of the air.

Soughing Wind. It was a theological image splendid beyond any ever conceived on this continent. For a great wind of the spirit soughed through the night of slavery and, as in Ezekiel’s vision, on the field of dead hope the dry bones stirred with life.

They kept stirring as, through the dismal years, the great hymnal testimonies moaned forth. Sometimes they were lyric visions of deliverance:

Swing low, sweet chariot,

Comin’ for to carry me home;

I look’d over Jordan,

And what did I see,

Comin’ for to carry me home,

A band of angels comin’ after me,

Comin’ for to carry me home.

Sometimes they were statements of bottomless sorrow:

Nobody knows de trouble I’ve seen,

Nobody knows but Jesus.

Sometimes they were rumbling adjurations:

Go down, Moses,

Way down in Egypt land,

Tell ol’ Pharaoh

To let my people go.

Sometimes they were simple longings:

Deep River, my home is over Jordan,

Deep River, Lord,

I want to cross over into camp ground.

Sometimes they were unsurpassed paeans of death:

Ezekiel weep, Ezekiel moan,

Flesh come acreepin’ of ol’ Ezekiel’s bones,

Church, I know you goin’ to miss me

when I’m gone.

When I’m gone, gone, gone.

When I’m gone to come no more,

Church, I know you goin’ to miss me

when I’m gone.

Always they were ringing assertions of faith:

I got a home in dat Rock, don’t you see?

I got a home in dat Rock, don’t you see?

Between de earth an’ Sky,

Thought I heard my Saviour cry,

You got a home in dat Rock, don’t you see?

The Magnificat of their music has sometimes obscured the poetry of the spirituals. There are few religious poems of any people that can equal this one:

I know moonrise, I know star-rise,

I lay dis body down.

I walk in de moonlight, I walk in de starlight,

To lay dis body, heah, down …

I lie in de grave an’ stretch out my arms,

I lay dis body, heah, down.

I go to judgment in de evenin’ of de day,

When I lay dis body down.

The problem of the white American and the Negro American has rarely been more simply evoked than in those last lines. The problem could be explained (and must in part be solved) in political, social and economic terms. But it is deeper than that, and so must its eventual solution be.

Well might all Americans, at Christmas, 1946, ponder upon the fact that it is, like all the great problems of mankind, at bottom a religious problem, and that the religious solution must be made before any other solutions could be effective. It will, in fact, never be solved exclusively in human terms.

Of the possible meaning of Negro Americans to all white Christians, Historian Arnold J. Toynbee wrote (in his monumental work-in-progress, A Study of History): “The Negro appears to be answering our tremendous challenge with a religious response which may prove in the event, when it can be seen in retrospect, to bear comparison with the ancient Oriental’s response to the challenge from his Roman masters. . . . Opening a simple and impressionable mind to the Gospels, he has divined the true nature of Jesus’ mission. He has understood that this was a prophet who came into the world not to confirm the mighty in their seat but to exalt the meek and the humble. . . . The Syrian slave-immigrants who once brought Christianity into Roman Italy performed the miracle of establishing a new religion which was alive in the place of an old religion which was already dead. It is possible that the Negro slave-immigrants who have found Christianity in America may perform the greater miracle of raising the dead to life. With their childlike intuition and their genius for giving spontaneous esthetic expression to emotional religious experience, they may perhaps be capable of rekindling the cold grey ashes of Christianity which have been transmitted to them by us, until in their hearts the divine fire glows again. It is thus, perhaps, if at all, that Christianity may conceivably become the living faith of a dying civilization for the second time. If this miracle were indeed to be performed by an American Negro Church, that would be the most dynamic response to the challenge of social penalization that had yet been made by Man.”

Go tell it on the mountain,

Over the hills and everywheah;

Go tell it on the mountain,

That Jesus Christ is aborn.

2 Responses to Religion: In Egypt Land (Marian Anderson)

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Archives

Tags

Adolf Berle Alexander Ulanovsky Alger Hiss Arthur Koestler Atlas Shrugged Ayn Rand Benn Steil Cold Friday Cold War Communism Dwight Eisenhower FDR George W. Bush Ghosts on the Roof Harry Dexter White Harry Truman Hiss Case House Un-American Activities Committee HUAC Ignatz Reiss John Loomis Sherman John Maynard Keynes Joseph McCarthy Joseph Stalin Karl Marx Leon Trotsky Max Bedacht Middle East National Review Peter the Great Pumpkin Papers Ralph de Toledano Richard Nixon Ronald Reagan Sputnik TIME magazine Tony Judt Vladimir Lenin Walter Krivitsky Westminster Whittaker Chambers William F. Buckley William F. Buckley Jr. Winston Churchill YaltaArt Resources

- B&W Photos from Farm Security Administration-Office of War Information Collection

- Life of the People: Radical Impulse + Capital and Labor

- Art of Marxism

- Comrades in Art

- Graphic Witness

- Jacob Burck

- Hugo Gellert + Gellert Papers

- William Gropper

- Jan Matulka: Thomas McCormick Gallery + Global Modernist

- Esther Shemitz Chambers

- Armory Show 1913

Pages from old website

Official website of Whittaker Chambers ( >> more )

Spycraft

- China Reporting

- CIA

- CIA – Alger Hiss Case

- Cold War Files

- Cold War Studies (Harvard)

- Comintern Online

- Comintern Online – LOC

- CWIHP – Wilson Center

- David Moore – Critical Thinking and Intelligence Analysis

- DC Writers: WC Home

- Economist – Espionage

- Essays on Espionage

- FBI – Rogue DNS Checker

- House – Hearing 08/25/1948

- House – Hiss Subpoena

- InfoRapid: WC

- Max Bedacht

- New York Times – Espionage

- NSA – FOIA Request

- PBS NOVA – Secrets Lies and Atomic Spies

- Richard Sorge

- Secrecy News

- Sherman Kent – Collected Essays

- Spy Museum – SPY Blog

- Thomas Sakmyster – J Peters

- Top Secret America – Map

- UK National Archives

- Vassiliev Notebooks

- Venona Decrypts

- Washington Decoded

- Washington Post – Espionage

- Zee Maps

Libraries

- American Commissar by Sandor Voros

- American Mercury – John Land

- American Writers Museum

- Archive.org – HUAC

- Archive.org – Lazar home

- Archive.org – Lazar Report

- Archives.org: 1948 – Hearings

- Archives.org: 1950 – Sherman Lieber

- Archives.org: 1951 – Sorge

- Archives.org: Ernie Lazar FOIA

- Archives.org: Ernie Lazar FOIA Collection

- Bio – Bennet Cerf

- Bio – Zara Witkin

- Bloomsburg University: Counterattack

- Bloomsburg University: Radical Publications

- Brooklyn Eagle 1948

- Centre des Archives communistes en Belgique

- CIA FOIA WC

- Daily Worker (various)

- Daily Worker: Marxists.org

- DC – Kudos

- DC – ORCID

- DC – ResearcherID

- DC – ResearchGate

- DC – SCOPUS

- Digital Public Library of America

- Erwin Marquit – Memoir

- FBI

- FBI Vault – WC

- Google: Books – WC

- GPO – WC

- GW – ER Papers: WC

- GWU: Eleanor Roosevelt WC

- Harvard College Writing Center – WC Summary

- Hathi: WC

- IISH: Marx Engels Papers

- ILGWU archives

- Images AP

- Images Corbis

- Images Getty Time Life

- Images LOC

- INKOMKA Comintern Archives

- International Newsletter of Communist Studies (Germany)

- JJC/CUNY – HC

- Labor Archives in the United States and Canada

- Life – WC

- LOC LCCN WC

- NBC Learn K-12: Spy Trials

- New Masses (Archive.org) 1926–1933

- New Masses (Marxists.org) 1926–1933

- New Masses (USussex) 1926–1938

- NSA: FOIA requests

- Ollie Atkins Photos

- Open Library: WC

- People: WC

- Poetry: Defeat in the Village

- PSA Communism

- SLU Law: HCase

- SSRN: Berresford – Hiss Case

- SUFL: Collections

- Tamiment: Collections

- Truman Library – John S. Service

- Truman Library – Oral Histories

- Truman Library – WC

- UCBerk * eBooks

- UCBerk: China – Edgar Snow

- UCBerk: China – Grace Service

- UCBerk: China – Kataoka

- UCBerk: China – Mackinnon

- UCBerk: China – Owen Lattimore

- UCBerk: China – Stross

- UCBerk: France – Revolution

- UCBerk: Russia – Bread 1914-1921

- UCBerk: Russia – Comintern

- UCBerk: US – Conservatism WC

- UCBerk: US – Hollywood Weimar

- UCBerk: US – James Joyce

- UCBerk: US – Lawyers

- UCBerk: US – NY Intellectual

- UCBerk: US – Waterfronts

- UCLA Library Film & TV Archive

- UK National Archives: WC

- UMich: Salant Deception

- UPenn: US – Left Ephemera Collection

- UPitt: US – Harry Gannes

- USDOE

- USDoED

- USDOJ

- USDOS

- Wall St + Bolshevik Revolution – Anthony Sutton

- Wikipedia A-D

- WikiSearch WC

- WordPress themes – Anders Noren

- x FSearch – WC

Magnificent!

[…] So much for 19th Century food fare in “Egypt Land.” […]