- Articles

- Commonweal

- TIME – Reviews

- TIME – Articles

- TIME – Cover Stories

- TIME – Foreign News

- Life Magazine

- Harper’s: A Chain is as Strong as its Most Confused Link

- TIME – Religion

- New York Tribune

- TIME

- National Review

- Soviet Strategy in the Middle East

- The Coming Struggle for Outer Space

- The Left Understands the Left

- To Temporize Is Death

- Big Sister Is Watching You

- Springhead to Springhead

- Some Untimely Jottings

- RIP: Virginia Freedom

- A Reminder

- A Republican Looks At His Vote

- Some Westminster Notes

- Missiles, Brains and Mind

- The Hissiad: A Correction

- Foot in the Door

- Books

- Poetry

- Video

- About

- Disclaimer

- Case

- Articles on the Case

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1948

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1949

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1950

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1951

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1952

- Trial by Typewriter

- I Was the Witness

- The Time News Quiz

- Another Witness

- Question of Security

- Fusilier

- Publican & Pharisee

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Kudos

- Letters – June 16, 1952

- Readable

- Letters – June 23, 1952

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Nominee for Veep

- Recent and Readable

- Recent and Readable

- Democratic Nominee for President

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Fighting Quaker

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Timely Saints

- Nixon on Communism

- People

- Who’s for Whom

- 1952 Bestsellers

- Letters – December 15, 1952

- Year in Books

- Man of Bretton Woods

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1953

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1954

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1955

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1956-1957

- Private

Books: Finnegan’s Wake

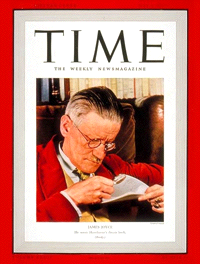

Monday, May. 08, 1939

BOOKS: Night Thoughts

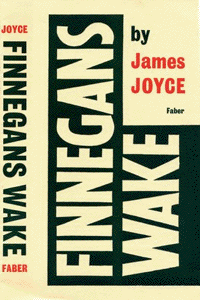

(See Cover) FINNEGANS WAKE — James Joyce — Viking ($5)

All children are afraid of the night; when they grow up, they are still afraid, but more afraid of admitting it. In this frightening darkness men lie down to sleep and dream. Generations of diviners, black magicians, fortune tellers and poets have made night and dreams their province, interpreting the troubled images that float through men’s sleeping minds as omens of good & evil. Only of late have psychologists asserted that dreams tell nothing about men’s future, much about their hidden or forgotten past. In dreams, this past floats, usually uncensored and distorted, to the surface of their slumbering consciousness.

All children are afraid of the night; when they grow up, they are still afraid, but more afraid of admitting it. In this frightening darkness men lie down to sleep and dream. Generations of diviners, black magicians, fortune tellers and poets have made night and dreams their province, interpreting the troubled images that float through men’s sleeping minds as omens of good & evil. Only of late have psychologists asserted that dreams tell nothing about men’s future, much about their hidden or forgotten past. In dreams, this past floats, usually uncensored and distorted, to the surface of their slumbering consciousness.

This week, for the first time, a writer had attempted to make articulate this wordless world of sleep. The writer is James Joyce; the book, Finnegans Wake — final title of his long-heralded Work in Progress. In his 57 years this erudite and fanciful Irishman, from homes in exile all over Europe, has written two books that have influenced the work of his contemporaries more than any others of his time: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, the best of innumerable novels picturing an artist’s struggle with his environment; Ulysses, considered baffling and obscure 15 years ago, now accepted as a modern masterpiece.

Finnegans Wake is a difficult book — too difficult for most people to read. In fact, it cannot be “read” in the ordinary sense. It is perhaps the most consciously obscure work that a man of acknowledged genius has produced. Its four sections run to 628 pages, and from its first line:

riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay

to its last:

A way a lone a last a loved a long the

there is not a sentence to guide the reader in interpreting it; there is not a single direct statement of what it is about, where its action takes place, what, in the simplest sense, it means.

It is packed with jokes, plays on words; it contains nonsensical diagrams, ridiculous footnotes, obscure allusions. Sometimes it seems to be retelling, in a chattering, stammering, incoherent way, the legends of Tristan and Isolde, of Wellington and Napoleon, Cain and Abel. Sometimes it seems to be a description, written with torrential eloquence, of the flow of a river to the sea.

As a gigantic laboratory experiment with language, Finnegans Wake is bound to exert an influence far beyond the circle of its immediate readers. Whether Joyce is eventually convicted of assaulting the King’s English with intent to kill or whether he has really added a cubit to her stature, she will never be quite the same again.

Title. The title of Finnegans Wake comes from an Irish music-hall ballad, telling how Tim Finnigan of Dublin’s Sackville Street, a hod carrier and “an Irish gentleman very odd” who loved his liquor, fell from his ladder one morning and broke his skull. His friends, thinking him dead, assembled for a wake, began to fight, weep, dance:

Whack Huno take your partner, Well the floor your trotters shake, Isn’t it the truth I tell you, Lots of fun at Finnigan’s Wake.

In the uproar, a gallon of whiskey is spilled on Tim, who comes to, saying,

Whirl your liquor round like blazes, Arrah gudaguddug do you think l’m dead?

On this old song Joyce has played a characteristic trick. Besides reminding readers that they are in for an Irish evening, his title might be taken as a simple declarative sentence meaning that Finnegans wake up. Hence the implication: ordinary people (such as his hero) do not; the nightmare existence of Everyman ends merely in a deeper sleep.

Story. As readers hack their way through the thorny pages of Finnegans Wake, they become aware of certain figures and phrases that recur frequently — H. C. Earwicker, Anna Livia, Maggie, Guinness, Phoenix Park, the River Liffey that curves through Dublin. Tracing these characters and places as they bob in and out of apparently unrelated words and sentences, Critic Edmund Wilson has worked out the most intelligible interpretation of the book, supported by Joyce’s own statement that, as Ulysses is a Dublin day, Finnegans Wake is a Dublin night. The long confused passages in which people change shape, the speeches that sound matter-of-fact but turn out to be gibberish, the flights, pursuits, embarrassing situations which are oddly taken for granted—all these are not mere plays on words or literary jokes; they are dreams.

Central figure appears to be a middle-aged Dubliner of Norwegian descent named H. C. Earwicker, once a postman, a shopkeeper, hotelkeeper, an employe of Guinness’ Brewery. He is married to a woman named Maggie, and father of several children, but involved in some way with a girl named Anna. Earwicker has been mixed up in some drunken misdemeanor, his dreams are filled with fears of being caught by the police. He dreams that he is coming out of a pub with his pals; a crowd gathers; one of the revelers sings a song, but it turns into a recital of Earwicker’s sins and folly. He dreams that he is called upon to explain the fable of “the Mookse and the Gripes”; as he begins, the Mookse comes swaggering up and attacks the Gripes, and suddenly Earwicker himself is going over one of his encounters with the police.

He changes shape in his dream: sometimes he is H. C. Earwicker, but sometimes he is Here Comes Everybody, or Haveth Childers Everywhere. Sometimes he is an old man, worried, half-sick, mixed up in vulgar and unpleasant affairs, sometimes his dreams spring back to his youth when he was, in Critic Wilson’s words, “carefree, attractive, well-liked … as dawn approaches, as he becomes dimly aware of the first light, the dream begins to brighten and to rise unencumbered.”

Earwicker’s dreams, like most people’s, are troubled by hints of depravity, but they remain hints. Even suggestive words are disguised. Is the book dirty? Censors will probably never be able to tell. Melting and merging in Earwicker’s dream-state, like smoke in a fog, readers sense Anna, the girl with whom he is in love: Anna on the riverbank, Anna Livia, Anna Livia Plurabelle. Through the menacing or ridiculous distortions of his dreams, the thought of Anna Livia breaks with singular lyric beauty.

There is no plot in the novel, no story in the usual sense of the word. What happens to Earwicker or what has happened to him—whether, indeed, he is as central a figure as he appears to be—is open to question: readers can construct a dozen theories to explain the form of the book, and find plausible evidence for each. Thus, it sometimes seems that sane speeches are not part of the dream, but voices from the waking world which dimly reach the sleeper. Sometimes it seems that he is hearing confused sounds of some turbulent life going on around him, which he dimly apprehends but in which he takes no part —as Finnigan might semiconsciously register the fighting and weeping over his bier. And there is a suggestion that as the dream ends, life itself ends, in the utter and profound sleep of death.

But however they interpret it, readers are not likely to miss the development in the rhythm and mood of the writing: the bobbing facetious note in the first passages; the clogged, heavy, stupefied quality that marks the middle section; the mood, half-exultation, half-sadness, on which it ends: “A hundred cares, a tithe of troubles and is there one who understands me? One in a thousand of years of the nights?”

Method. Joyce’s idea in Finnegans Wake is not new. More than a hundred years ago, when Nathaniel Hawthorne was living in Salem, he jotted in his notebook an idea for a story: “To write a dream which shall resemble the real course of a dream, with all its inconsistency, its strange transformations . . . with nevertheless a leading idea running through the whole. Up to this old age of the world, no such thing has ever been written.”

But Joyce’s method is new. Dreams exist as sensation or impression, not as speech. Words are spoken in dreams, but they are usually not the words of waking life, may be capable of multiple meanings, or may even be understood in several different senses by the same dreamer at the same moment. Since dreams take place in a state of suspended consciousness, out of which language itself arises, Joyce creates, in Finnegans Wake, a dream language to communicate the dream itself.

Compounded of puns, disjointed syllables, half-words, it is closest to English, but Erse, Latin, Greek, Dutch, French, Sanskrit, even Esperanto appear, usually distorted to suggest both an alien and an English notion. The ablest punster in seven languages, Joyce sometimes combines puns and snatches of songs. Example: “ginabawdy meadabawdy!” (from a passage dealing with Earwicker’s dream of a night out). Using a favorite device, he suggests that Anna Livia is the River Liffey by slyly punning on the names of other rivers: “he gave her the tigris eye,” “rubbing the mouldaw stains,” “And the dneepers of wet and the gangres of sin in it”—for the Tigris, Moldau, Dnieper and Ganges. 1

Readers who like plain-spoken words may grow impatient, but lovers of words for themselves will find in Finnegans Wake some lyric passages to make them sit up:

“Can’t hear with the waters of. The chittering waters of. Flittering bats, field-mice bawk talk. Ho! Are you not gone ahome? What Thorn Malone? Can’t hear with bawk of bats, all thim liffeying waters of. Ho, talk save us! My foos won’t moos. I feel as old as yonder elm. A tale told of Shaun or Shem? All Livia’s daughter-sons. Dark hawks hear us. Night! Night! My ho head halls. I feel as heavy as yonder stone. Tell me of John or Shaun? Who were Shem and Shaun the living sons or daughters of? Night now! Tell me, tell me, tell me, elm! Night night! Telmetale of stem or stone. Beside the rivering waters of, hitherandthithering waters of. Night!”

The Author. With the publication of Finnegans Wake, James Joyce has probably closed the cycle of his great works. Ulysses took seven years to write, Finnegans Wake, 17. At this rate of progression another book would take 41 years, making Joyce 98 when it was finished.

Joyce left Ireland (“the old sow that eats her farrow”) 35 years ago and went to Trieste, then in Austria-Hungary, to live by “silence, exile and cunning.” In Trieste his children were born. In 1915 Joyce was so busy with Ulysses that he scarcely noticed that Italy and Austria were about to fight until frontiers began to close. A Greek friend (Joyce is superstitious about Greeks, believes that they bring him luck, that nuns do not) got him permission to leave through Italy. Along the frontier, each time he passed a station, it was dynamited behind him.

Resettled at Zurich, Joyce taught at the Berlitz school, as he had at Trieste. Mrs. Joyce remembers poverty and small apartments, “long on mice, short on kitchen utensils.” But Joyce was happy, worked hard on Ulysses, enjoyed drinking white wine with English Painter Frank Budgen at the Cafe Pfauen. Lenin used to frequent the same cafe, but the literary and the proletarian revolutionists never met.

Joyce’s admirers, George Moore, W. B. Yeats, Edmund Gosse, meanwhile began to worry about his perennial poverty, succeeded in getting him £100 from the Privy Purse, thought that Joyce should show his gratitude by aiding the Allied cause. Joyce, who was under oath to the Austrians not to bear arms and is resolutely unpolitical, thought he did enough by spreading British culture. He founded the English Players and put on his play Exiles.

The annoying War over, Joyce returned to Trieste, but the Italians had got there first. There was constant turmoil while one of Joyce’s favorite authors, Commendatore Gabriele D’Annunzio, seized nearby Fiume. So in 1920 Joyce took his family to Paris, where he has lived almost continuously since.

Europe in 1920 was still a shell-shocked continent in a state of suspended war. It was impossible to travel in most directions without traveling through armies, or in northern France and Belgium through heaped wreckage and broken walls. Revolutions threatened and populations starved. Joyce in Paris was close to starving too. But help came to him from U. S. and English expatriates. American Poet Robert McAlmon lent him money, Bookshop Owner Sylvia Beach began publishing Ulysses. Ezra Pound, Idaho’s great expatriate, introduced him to Harriet Weaver.

Owner of the Egoist Press, publisher of The Egoist, Harriet Weaver was a shy little wisp of a woman, terrified by the dramatic manners of the literary great she patronized. She has been called “an authentic but difficult saint.” To Joyce she proved an angel. In 1922, to assure him complete peace of mind and concentration on his work, Egoist Weaver gave him a large sum of money outright. Most reliable information puts it at £40,000 (about $200,000). With this gift Joyce’s biography becomes largely a bibliography.

Nono. In appearance Joyce is slight, frail but impressive. He stands five feet ten or eleven, but looks as if a strong wind might blow him down. His face is thin and fine, its profile especially delicate. He wears his greying, thinning hair brushed back without a part. Joyce reads and writes sprawling in bed or on a couch but he does not like it known. He is very formal in public, in restaurants prefers straight-back chairs in which he sits bolt upright.

He dresses with conservative elegance, never goes out without a slender walking stick, which he manipulates expertly, accenting the delicacy of his beringed hands (he has a passion for rings). His voice is soft, rich and low with a gentle, melancholy brogue. He is rather vain of his tenor, which he likes to join with his son’s bass at small family celebrations.

Joyce’s curious glasses give him a somewhat Martian appearance. The left lens is so thick it is almost a hemisphere, and to focus it is necessary for him to throw back his head slightly when looking at people. Ten years ago, Joyce could not see with his left eye at all, and a cataract was beginning to form on the right eye. Every operation on the left eye caused a hemorrhage. Finally Dr. Alfred Vogt of Zurich succeeded in making an artificial pupil for the left eye, set in below the position of the normal pupil. The cataract on Joyce’s right eye has meanwhile developed. He has had eleven major operations on his eyes, all without anesthetics, faces another soon. But he sees far better than he did ten years ago.

The Joyce family consists of amiable Galway wife Nora, née Barnacle; a son, Giorgio, 33; a dancer-illustrator daughter, Lucia, thirtyish. Giorgio, who married American Helen Gastor, has one son, Stephen James, lives in a Paris suburb where Joyce and his wife frequently visit him. Grandson Stephen is adored by his grandfather, calls the author of Ulysses “Nono.”

Among Joyce’s closest friends are Eugene Jolas (editor of transition), Paul Léon, his secretary, and Stuart Gilbert, who wrote an exhaustive exegesis of Ulysses. With Eugene and Maria Jolas, the Joyces dine every Saturday night.

Joyce is constantly jotting down overheard phrases, is especially interested in dialects, Midwestern American, British colonial, newspaper jargon. He speaks Italian as smoothly as English, flawless French, fluent German, knows some dozen other tongues, including outlandish Lapp. At present Joyce is not writing. His wife is trying to get him started on something, because when he is not working he is hard to live with.

Though he has been away from Ireland since 1904, returning only briefly in 1912 to start a motion-picture house, the Volta, which quickly failed, Joyce has an unrivaled knowledge of Dublin and its current life, keeps his recollections green by subscribing to Dublin newspapers, pores over their gossip and chitchat.

But no observer of his life and works can fail to note that James Joyce is a typical Irishman. Born in Dublin, he remains as Irish in Paris or Trieste as he was in the city of his birth. His friends believe that nothing short of a European war could drive him back to the “little brown bog” and the haunting Liffey.

Notes:

- Doodling statisticians have counted up names of 700 rivers in the 20-page Anna Livia section. [This is Time‘s footnote – Editor] ↩

Archives

Tags

Adolf Berle Alexander Ulanovsky Alger Hiss Arthur Koestler Atlas Shrugged Ayn Rand Benn Steil Cold Friday Cold War Communism Dwight Eisenhower FDR George W. Bush Ghosts on the Roof Harry Dexter White Harry Truman Hiss Case House Un-American Activities Committee HUAC Ignatz Reiss John Loomis Sherman John Maynard Keynes Joseph McCarthy Joseph Stalin Karl Marx Leon Trotsky Max Bedacht Middle East National Review Peter the Great Pumpkin Papers Ralph de Toledano Richard Nixon Ronald Reagan Sputnik TIME magazine Tony Judt Vladimir Lenin Walter Krivitsky Westminster Whittaker Chambers William F. Buckley William F. Buckley Jr. Winston Churchill YaltaArt Resources

- B&W Photos from Farm Security Administration-Office of War Information Collection

- Life of the People: Radical Impulse + Capital and Labor

- Art of Marxism

- Comrades in Art

- Graphic Witness

- Jacob Burck

- Hugo Gellert + Gellert Papers

- William Gropper

- Jan Matulka: Thomas McCormick Gallery + Global Modernist

- Esther Shemitz Chambers

- Armory Show 1913

Pages from old website

Official website of Whittaker Chambers ( >> more )

Spycraft

- China Reporting

- CIA

- CIA – Alger Hiss Case

- Cold War Files

- Cold War Studies (Harvard)

- Comintern Online

- Comintern Online – LOC

- CWIHP – Wilson Center

- David Moore – Critical Thinking and Intelligence Analysis

- DC Writers: WC Home

- Economist – Espionage

- Essays on Espionage

- FBI – Rogue DNS Checker

- House – Hearing 08/25/1948

- House – Hiss Subpoena

- InfoRapid: WC

- Max Bedacht

- New York Times – Espionage

- NSA – FOIA Request

- PBS NOVA – Secrets Lies and Atomic Spies

- Richard Sorge

- Secrecy News

- Sherman Kent – Collected Essays

- Spy Museum – SPY Blog

- Thomas Sakmyster – J Peters

- Top Secret America – Map

- UK National Archives

- Vassiliev Notebooks

- Venona Decrypts

- Washington Decoded

- Washington Post – Espionage

- Zee Maps

Libraries

- American Commissar by Sandor Voros

- American Mercury – John Land

- American Writers Museum

- Archive.org – HUAC

- Archive.org – Lazar home

- Archive.org – Lazar Report

- Archives.org: 1948 – Hearings

- Archives.org: 1950 – Sherman Lieber

- Archives.org: 1951 – Sorge

- Archives.org: Ernie Lazar FOIA

- Archives.org: Ernie Lazar FOIA Collection

- Bio – Bennet Cerf

- Bio – Zara Witkin

- Bloomsburg University: Counterattack

- Bloomsburg University: Radical Publications

- Brooklyn Eagle 1948

- Centre des Archives communistes en Belgique

- CIA FOIA WC

- Daily Worker (various)

- Daily Worker: Marxists.org

- DC – Kudos

- DC – ORCID

- DC – ResearcherID

- DC – ResearchGate

- DC – SCOPUS

- Digital Public Library of America

- Erwin Marquit – Memoir

- FBI

- FBI Vault – WC

- Google: Books – WC

- GPO – WC

- GW – ER Papers: WC

- GWU: Eleanor Roosevelt WC

- Harvard College Writing Center – WC Summary

- Hathi: WC

- IISH: Marx Engels Papers

- ILGWU archives

- Images AP

- Images Corbis

- Images Getty Time Life

- Images LOC

- INKOMKA Comintern Archives

- International Newsletter of Communist Studies (Germany)

- JJC/CUNY – HC

- Labor Archives in the United States and Canada

- Life – WC

- LOC LCCN WC

- NBC Learn K-12: Spy Trials

- New Masses (Archive.org) 1926–1933

- New Masses (Marxists.org) 1926–1933

- New Masses (USussex) 1926–1938

- NSA: FOIA requests

- Ollie Atkins Photos

- Open Library: WC

- People: WC

- Poetry: Defeat in the Village

- PSA Communism

- SLU Law: HCase

- SSRN: Berresford – Hiss Case

- SUFL: Collections

- Tamiment: Collections

- Truman Library – John S. Service

- Truman Library – Oral Histories

- Truman Library – WC

- UCBerk * eBooks

- UCBerk: China – Edgar Snow

- UCBerk: China – Grace Service

- UCBerk: China – Kataoka

- UCBerk: China – Mackinnon

- UCBerk: China – Owen Lattimore

- UCBerk: China – Stross

- UCBerk: France – Revolution

- UCBerk: Russia – Bread 1914-1921

- UCBerk: Russia – Comintern

- UCBerk: US – Conservatism WC

- UCBerk: US – Hollywood Weimar

- UCBerk: US – James Joyce

- UCBerk: US – Lawyers

- UCBerk: US – NY Intellectual

- UCBerk: US – Waterfronts

- UCLA Library Film & TV Archive

- UK National Archives: WC

- UMich: Salant Deception

- UPenn: US – Left Ephemera Collection

- UPitt: US – Harry Gannes

- USDOE

- USDoED

- USDOJ

- USDOS

- Wall St + Bolshevik Revolution – Anthony Sutton

- Wikipedia A-D

- WikiSearch WC

- WordPress themes – Anders Noren

- x FSearch – WC