- Articles

- Commonweal

- TIME – Reviews

- TIME – Articles

- TIME – Cover Stories

- TIME – Foreign News

- Life Magazine

- Harper’s: A Chain is as Strong as its Most Confused Link

- TIME – Religion

- New York Tribune

- TIME

- National Review

- Soviet Strategy in the Middle East

- The Coming Struggle for Outer Space

- The Left Understands the Left

- To Temporize Is Death

- Big Sister Is Watching You

- Springhead to Springhead

- Some Untimely Jottings

- RIP: Virginia Freedom

- A Reminder

- A Republican Looks At His Vote

- Some Westminster Notes

- Missiles, Brains and Mind

- The Hissiad: A Correction

- Foot in the Door

- Books

- Poetry

- Video

- About

- Disclaimer

- Case

- Articles on the Case

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1948

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1949

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1950

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1951

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1952

- Trial by Typewriter

- I Was the Witness

- The Time News Quiz

- Another Witness

- Question of Security

- Fusilier

- Publican & Pharisee

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Kudos

- Letters – June 16, 1952

- Readable

- Letters – June 23, 1952

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Nominee for Veep

- Recent and Readable

- Recent and Readable

- Democratic Nominee for President

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Fighting Quaker

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Timely Saints

- Nixon on Communism

- People

- Who’s for Whom

- 1952 Bestsellers

- Letters – December 15, 1952

- Year in Books

- Man of Bretton Woods

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1953

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1954

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1955

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1956-1957

- Private

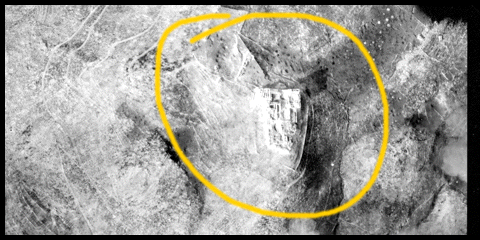

The Bombing of Monte Cassino

Monday, Feb. 28, 1944

The Bombing of Monte Cassino

The meaning of the Cassino Monastery Incident was 80 miles north in Rome. Must the Allies bomb St. Peter’s into rubble and then fight their way, chapel by chapel, through the Vatican?

In the valley below Mt. Cassino an American artillery-battery commander spoke: “I don’t give a damn about the monastery. I have Catholic gunners in this battery and they’ve asked me for permission to fire on it, but I haven’t been able to give it to them. They don’t like it.”

The Germans were using the famed 1,400-year-old Benedictine abbey as an artillery-observation post. This seemed well established, as hundreds of young Americans died on the slope below. Collier’s War Correspondent Frank Gervasi reported: “I saw 800 [Americans] go out and 24 come back, because the Germans could see every move and turn their fire on them.” And the Germans, after noting heavy, bloody U.S. losses, laconically reported in a communiqué that Indian Gurkha troops had replaced “the worn-out Americans.”

The slaughter grew too great. After weeks of soul searching and delay, the Allies decided to bomb and to shell the abbey. They followed a Dec. 29, 1943 order of General Dwight Eisenhower: “We are fighting in a country … rich in monuments which illustrate the growth of the civilization which is ours. We are bound to respect those monuments so far as war allows. If we have to choose between destroying a famous building and sacrificing our own men, then our men’s lives count infinitely more, and the buildings must go.”

On a sunlit morning last week the buildings went.

“That’s Beautiful.” In the Liri Valley, thousands of U.S. soldiers, whose buddies had died on the slope, watched. Then, at 9:28 a.m., from beyond the snow-capped peaks, came the first wave of lordly Fortresses. From the mountain peak came great orange bursts of flame, billowing smoke. The muffled crunch of explosions grew like a roll of thunder.

Three minutes later came more Fortresses; the third wave at 9:45. Watching the precision bombing, a U.S. general cried: “That’s beautiful.” He seemed to want to direct the planes: “That’s the way. Keep them over to the left. Oh, oh, that one’s a little bit close. That’s better. Oh, that’s beautiful.”

The bombers came on, 226 of them, Fortresses, Liberators, Mitchells and Marauders, roaming the cloudless sky undisturbed, dropping their bombs with exquisite exactness. Between the waves of bombers the artillery Long’ Toms and 240-mm. howitzers pumped shells up the hill. The mountain seemed to jump and quiver, like a great bear twitching in sleep. Observers counted 200 men, some allegedly in uniform, scurrying out of the devastated monastery. As the next-to-last wave of 20 Marauders dropped a cluster smack on the abbey, an American soldier yelled: “Touchdown.”

Thus the great Benedictine abbey, built 400 years ago on ground where Benedictine abbeys had stood for 1,400 years, was demolished. Only one wall section remained standing, and the next day Marauders swooped over to pick these ribs.

The Americans got no forwarder. If there had been no Germans there before, there were now. The Nazis moved swiftly into the ruins, to defend them in the best Stalingrad fashion. Soon out of the rubble pricked scores of gun barrels.

Down from the abbey trickled pitiful refugees, Italians caught in no man’s land. They had been panicked by an Allied artillery warning of shells that exploded in a shower of leaflets warning of the coming bombing. The Germans had refused to let them leave the abbey. But the refugees, who said German machine guns were at every door, did not say that Germans had been in the abbey.

“Succisa Virescit.” Said the German radio: “Outrage.” For two days Nazi communiques flatly stated that there had been no German soldiers within the abbey or in its immediate vicinity. Said Field Marshal Albert Kesselring: “I have only the deepest contempt for the cynical mendacity and sanctimonious pictures with which the Anglo-Saxon Commands now attempt to make me responsible for their acts.”

Radio Berlin next reported that Harold Tittmann, the U.S. Chargé D’affaires at the Vatican, had informed Cardinal Maglione, Papal Secretary of State, that the U.S. would rebuild the monastery. The Cardinal was supposed to have replied: “Even if you rebuild it in gold and diamonds, it still isn’t the monastery.”

But everywhere in Allied countries, leaders of all faiths accepted the destruction of the monastery in good faith that its destruction had been necessary. Said Archbishop Michael J. Curley of Baltimore: “Every Catholic throughout the world will understand.” Wrote the Rt. Rev. Stephen Schappler, Abbott of Conception Abbey at Conception, Mo.: “True to the device on her coat of arms, Succisa Virescit (when cut down, it grows again), the Abbey of Abbeys will have a rebirth. For that right our own boys are giving their all. Benedictines the world over are grateful to them.”

President Roosevelt expressed his regret at the act. But, he said, it had to be done.

Monument by Monument. But dust had not freshly settled over the Cassino abbey before the Allies faced another monument. Allied GHQ in Algiers announced that Castel Gandolfo, the Pope’s summer palace, approximately twelve miles north of the Anzio beachhead, “contained a heavy saturation of Nazis.” Five days later, Rome announced that Castel Gandolfo had again been bombed.

This time the Allied allegations were flatly denied by the highest Roman Catholic sources. In Washington, the Most Rev. Amleto Giovanni Cicognani, 1 Apostolic Delegate to the U.S. since 1933, stated, on instructions of Cardinal Maglione, that “no German soldier has been admitted within the borders of the neutral pontifical villa.” The National Catholic Welfare Conference then issued a statement that Castel Gandolfo was filled with 15,000 Italian refugees, “several hundred” of whom had been killed in recent Allied bombings.

http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,796392,00.html

Notes:

- Mgr. Cicognani is the personal representative of the Pope to the U.S. Government. He shuns the press, lives quietly in the $1,000,000 Apostolic Delegation on Washington’s swank Em bassy Row–Note from TIME magazine – Editor ↩

One Response to The Bombing of Monte Cassino

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Archives

Tags

Adolf Berle Alexander Ulanovsky Alger Hiss Arthur Koestler Atlas Shrugged Ayn Rand Benn Steil Cold Friday Cold War Communism Dwight Eisenhower FDR George W. Bush Ghosts on the Roof Harry Dexter White Harry Truman Hiss Case House Un-American Activities Committee HUAC Ignatz Reiss John Loomis Sherman John Maynard Keynes Joseph McCarthy Joseph Stalin Karl Marx Leon Trotsky Max Bedacht Middle East National Review Peter the Great Pumpkin Papers Ralph de Toledano Richard Nixon Ronald Reagan Sputnik TIME magazine Tony Judt Vladimir Lenin Walter Krivitsky Westminster Whittaker Chambers William F. Buckley William F. Buckley Jr. Winston Churchill YaltaArt Resources

- B&W Photos from Farm Security Administration-Office of War Information Collection

- Life of the People: Radical Impulse + Capital and Labor

- Art of Marxism

- Comrades in Art

- Graphic Witness

- Jacob Burck

- Hugo Gellert + Gellert Papers

- William Gropper

- Jan Matulka: Thomas McCormick Gallery + Global Modernist

- Esther Shemitz Chambers

- Armory Show 1913

Pages from old website

Official website of Whittaker Chambers ( >> more )

Spycraft

- China Reporting

- CIA

- CIA – Alger Hiss Case

- Cold War Files

- Cold War Studies (Harvard)

- Comintern Online

- Comintern Online – LOC

- CWIHP – Wilson Center

- David Moore – Critical Thinking and Intelligence Analysis

- DC Writers: WC Home

- Economist – Espionage

- Essays on Espionage

- FBI – Rogue DNS Checker

- House – Hearing 08/25/1948

- House – Hiss Subpoena

- InfoRapid: WC

- Max Bedacht

- New York Times – Espionage

- NSA – FOIA Request

- PBS NOVA – Secrets Lies and Atomic Spies

- Richard Sorge

- Secrecy News

- Sherman Kent – Collected Essays

- Spy Museum – SPY Blog

- Thomas Sakmyster – J Peters

- Top Secret America – Map

- UK National Archives

- Vassiliev Notebooks

- Venona Decrypts

- Washington Decoded

- Washington Post – Espionage

- Zee Maps

Libraries

- American Commissar by Sandor Voros

- American Mercury – John Land

- American Writers Museum

- Archive.org – HUAC

- Archive.org – Lazar home

- Archive.org – Lazar Report

- Archives.org: 1948 – Hearings

- Archives.org: 1950 – Sherman Lieber

- Archives.org: 1951 – Sorge

- Archives.org: Ernie Lazar FOIA

- Archives.org: Ernie Lazar FOIA Collection

- Bio – Bennet Cerf

- Bio – Zara Witkin

- Bloomsburg University: Counterattack

- Bloomsburg University: Radical Publications

- Brooklyn Eagle 1948

- Centre des Archives communistes en Belgique

- CIA FOIA WC

- Daily Worker (various)

- Daily Worker: Marxists.org

- DC – Kudos

- DC – ORCID

- DC – ResearcherID

- DC – ResearchGate

- DC – SCOPUS

- Digital Public Library of America

- Erwin Marquit – Memoir

- FBI

- FBI Vault – WC

- Google: Books – WC

- GPO – WC

- GW – ER Papers: WC

- GWU: Eleanor Roosevelt WC

- Harvard College Writing Center – WC Summary

- Hathi: WC

- IISH: Marx Engels Papers

- ILGWU archives

- Images AP

- Images Corbis

- Images Getty Time Life

- Images LOC

- INKOMKA Comintern Archives

- International Newsletter of Communist Studies (Germany)

- JJC/CUNY – HC

- Labor Archives in the United States and Canada

- Life – WC

- LOC LCCN WC

- NBC Learn K-12: Spy Trials

- New Masses (Archive.org) 1926–1933

- New Masses (Marxists.org) 1926–1933

- New Masses (USussex) 1926–1938

- NSA: FOIA requests

- Ollie Atkins Photos

- Open Library: WC

- People: WC

- Poetry: Defeat in the Village

- PSA Communism

- SLU Law: HCase

- SSRN: Berresford – Hiss Case

- SUFL: Collections

- Tamiment: Collections

- Truman Library – John S. Service

- Truman Library – Oral Histories

- Truman Library – WC

- UCBerk * eBooks

- UCBerk: China – Edgar Snow

- UCBerk: China – Grace Service

- UCBerk: China – Kataoka

- UCBerk: China – Mackinnon

- UCBerk: China – Owen Lattimore

- UCBerk: China – Stross

- UCBerk: France – Revolution

- UCBerk: Russia – Bread 1914-1921

- UCBerk: Russia – Comintern

- UCBerk: US – Conservatism WC

- UCBerk: US – Hollywood Weimar

- UCBerk: US – James Joyce

- UCBerk: US – Lawyers

- UCBerk: US – NY Intellectual

- UCBerk: US – Waterfronts

- UCLA Library Film & TV Archive

- UK National Archives: WC

- UMich: Salant Deception

- UPenn: US – Left Ephemera Collection

- UPitt: US – Harry Gannes

- USDOE

- USDoED

- USDOJ

- USDOS

- Wall St + Bolshevik Revolution – Anthony Sutton

- Wikipedia A-D

- WikiSearch WC

- WordPress themes – Anders Noren

- x FSearch – WC

[…] The Bombing of Monte Cassino […]