- Articles

- Commonweal

- TIME – Reviews

- TIME – Articles

- TIME – Cover Stories

- TIME – Foreign News

- Life Magazine

- Harper’s: A Chain is as Strong as its Most Confused Link

- TIME – Religion

- New York Tribune

- TIME

- National Review

- Soviet Strategy in the Middle East

- The Coming Struggle for Outer Space

- The Left Understands the Left

- To Temporize Is Death

- Big Sister Is Watching You

- Springhead to Springhead

- Some Untimely Jottings

- RIP: Virginia Freedom

- A Reminder

- A Republican Looks At His Vote

- Some Westminster Notes

- Missiles, Brains and Mind

- The Hissiad: A Correction

- Foot in the Door

- Books

- Poetry

- Video

- About

- Disclaimer

- Case

- Articles on the Case

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1948

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1949

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1950

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1951

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1952

- Trial by Typewriter

- I Was the Witness

- The Time News Quiz

- Another Witness

- Question of Security

- Fusilier

- Publican & Pharisee

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Kudos

- Letters – June 16, 1952

- Readable

- Letters – June 23, 1952

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Nominee for Veep

- Recent and Readable

- Recent and Readable

- Democratic Nominee for President

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Fighting Quaker

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Timely Saints

- Nixon on Communism

- People

- Who’s for Whom

- 1952 Bestsellers

- Letters – December 15, 1952

- Year in Books

- Man of Bretton Woods

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1953

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1954

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1955

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1956-1957

- Private

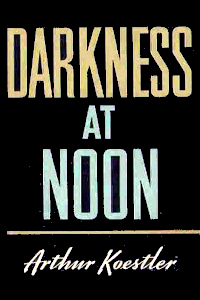

Books: Darkness at Noon

Monday, May. 26, 1941

Books: Brightest in Dungeons

Darkness at Noon — Arthur Koestler — Macmillan ($2.50)

Of Author Arthur Koestler little is definitely known. (He is said to be in London.) But he has written the most exciting novel of the season. As a war correspondent in Spain, he was captured by the Fascists, sentenced to death and released when the British Government intervened; in Cairo he once edited a German-Arabic weekly; in Haifa he once hawked lemonade in the streets. In 1939 he published a historical novel, The Gladiators, about the Spartacus revolt. From Darkness at Noon, it is obvious that he also knows Russia and the deep places of the human mind.

Of Author Arthur Koestler little is definitely known. (He is said to be in London.) But he has written the most exciting novel of the season. As a war correspondent in Spain, he was captured by the Fascists, sentenced to death and released when the British Government intervened; in Cairo he once edited a German-Arabic weekly; in Haifa he once hawked lemonade in the streets. In 1939 he published a historical novel, The Gladiators, about the Spartacus revolt. From Darkness at Noon, it is obvious that he also knows Russia and the deep places of the human mind.

The book begins with the clang of a cell door closing in a GPU prison. It ends with a shot in the back of the head in a murky passageway of the prison cellar. It moves with the speed, directness, precision and some of the impact of a bullet. More plausibly than any other book yet written, fiction or nonfiction, it gives the answer to one of history’s great riddles: Why do Russians confess?

Old Bolshevik Nicolas Rubashov, former People’s Commissar, former commander in the Red Army, a fictional composite of the late liquidated Leo Kamenev and Nikolai Bukharin, is broken down by the GPU, induced to sign a false confession and declare at a public trial that he had plotted to murder “No. 1” — Stalin. Penalty: “physical liquidation.” The men who succeeded in making old Rubashov confess (“To have laid out a Rubashov meant the beginning of a great career”) were GPU Inquisitors Ivanov and Gletkin. Ivanov had been Rubashov’s former schoolmate, former battalion commander. He drank, he doped a little, “but the vice of pity I have up till now managed to avoid. The smallest dose of it, and you are lost … The temptations of God were always more dangerous for mankind than those of Satan.”

Gletkin was a Stalinist, one of those humorless men whom Rubashov called the “Neanderthalers.” It took Rubashov some time to find the right words to describe Gletkin’s special quality: “correct brutality.” He had been a mere boy when the Revolution broke out. “That was the generation which had started to think after the flood. It had no traditions, and no memories … It was a generation born without umbilical cord …”

Ivanov was against using the “hard method” on Rubashov. “When Rubashov capitulates,” Ivanov told Gletkin, “it won’t be out of cowardice, but by logic. It is no use trying the hard method with him. He is made of a certain material which becomes the tougher the more you hammer on it.”

Said Gletkin: “That is just talk. Human beings able to resist any amount of physical pressure do not exist …”

“I wouldn’t like to fall into your hands'” said Ivanov, smilingly, but with a trace of uneasiness. Later he did.

The brilliant and terrible inquisitorial conversations, in which Ivanov and Gletkin try to make the old Bolshevik confess, have the suspense and pace of fast action. Equally expert is the statement of position which Author Koestler writes into Rubashov’s diary for him and which is Rubashov’s epitaph:

A short time ago, our leading agriculturalist, B., was shot with thirty of his collaborators because he maintained the opinion that nitrate artificial manure was superior to potash. No. 1 is all for potash; therefore B. and the thirty had to be liquidated as saboteurs. In a nationally centralized agriculture, the alternative of nitrate or potash is of enormous importance : it can decide the issue of the next war. If No. 1 was in the right, history will absolve him … If he was wrong … It is that alone that matters: who is objectively in the right … For us the question of subjective good faith is of no interest …

Rubashov knows there are only two possible ethical positions: “one of them is Christian and humane, declares the individual to be sacrosanct … The other starts from the basic principle that a collective aim justifies all means, and not only allows, but demands, that the individual should in every way be … sacrificed to the community …”

Not Rubashov and not Gletkin, but the man who incarnates the humane, discarded ethic is the hero of Darkness at Noon. He has no name, but a cell number, No. 402. He never appears in the novel. The only description of him is what Rubashov imagines he looks like. He has no voice. All he is, feels, fears, stands for, he can communicate only by tapping on the cell wall. He is the wraith of a cause which survives only, like a Marxist antithesis, in the prison where Marxists think they have buried it. Among a population of logical monsters, he is the only fallible human being.

No. 402 began to tap shortly after Rubashov moved in. WHO? he tapped, using the old revolutionist’s code. “Well why not?” thought Rubashov self-importantly, tapped out his full name. There was no answer. Suddenly No. 402 began to tap again, evidently using his shoe to make it louder: LONG LIVE H.M. THE EMPEROR!

Later, when Rubashov tapped: HAVE YOU ANY TOBACCO?, No. 402 tapped slowly and carefully: NOT FOR YOU. Rubashov was hurt. He could imagine the young Tsarist officer with a grin on his face and a monocle stuck in his eye. Probably he had lit a cigaret and was blowing the smoke against the wall. “Yes, how many of yours have I had shot?” Rubashov could scarcely remember—”something between seventy and a hundred … and he would do it again today.” Then he heard No. 402 tapping: SENDING YOU TOBACCO.

Sometimes No. 402 begged for conversation: DO TALK TO ME … He had an erotic turn, liked to tell stale jokes from the officers’ mess. After the jokes there would be a painful silence. Out of politeness, Rubashov sometimes tapped a loud, HA! HA!

One of these tapping scenes is among the finest in any recent writing. Rubashov could not sleep. Though it was late, he tapped to No. 402: ARE YOU ASLEEP? At first there was no answer, then No. 402 tapped: NO. DO YOU FEEL IT TOO? FEEL WHAT? asked Rubashov. Again No. 402 hesitated for a while. “Then he tapped so subduedly that it sounded as if he were speaking in a very low voice: IT’S BETTER FOR YOU TO SLEEP … TONIGHT POLITICAL DIFFERENCES ARE BEING SETTLED.”

EXECUTIONS? Rubashov lay down and waited. Suddenly No. 402 tapped loudly: NO. 380. PASS IT ON. “Rubashov sat up quickly. He understood: … The occupants of the cells between 380 and 402 formed an acoustic relay through darkness and silence … Rubashov jumped from his bunk, pattered over barefooted to the other wall, posted himself next to the bucket, and tapped to No. 406: ATTENTION. NO. 380 IS TO BE SHOT NOW. PASS IT ON.” To No. 402 Rubashov tapped: WHO is NO. 380? There was no answer. “Rubashov guessed that, like himself, No. 420 was moving pendulumlike between the two walls of his cell. . . .

“Now No. 402 was back again … THEY ARE READING THE SENTENCE TO HIM. PASS IT ON.” There was no use passing on the message to No. 406, whom the others believed insane, yet Rubashov tapped it through. “He was driven by an obscure … feeling that the chain must not be broken … Still not the slightest sound was heard from outside. Only the wall went on ticking: HE IS SHOUTING FOR HELP. HE IS SHOUTING FOR HELP. Rubashov tapped to No. 406 …

“WHAT IS HIS NAME?” Rubashov tapped quickly … BOGROV. OPPOSSITIONAL. PASS IT ON. Rubashov’s legs suddenly became heavy. He leaned against the wall and tapped through to No. 406: MICHAEL BOGROV. FORMER SAILOR ON BATTLESHIP POTEMKIN, COMMANDER OF THE EASTERN FLEET, BEARER OF THE FIRST REVOLUTIONARY ORDER, LED TO EXECUTION. He wiped the sweat from his forehead, was sick into the buckeT and ended his sentence: PASS IT ON.”

In his memory “he saw the outlines of [Bogrov’s] gigantic figure … they had been roommates in exile after 1905; Tubashov had taught hime reading, writing and the fundamentals of historical thought; since then, wherever Rubashov might happen to be, he received twice a year a hand-written letter, ending invariably with the words: ‘Your comrade, faithful unto the grave, Bogrov.'”

THEY ARE COMING, tapped No. 402 … STAND AT THE SPYHOLE. DRUM … Rubashov stood with his eyes pressed tothe spyhole, and joined the chorus by beating with both hands rhythmically against the concrete door … He gradually lost the sense of time and space, he heard only the hollow beating as of jungle tom-toms; it might have been apes that stood behind the bars of their cages, beating their chests and drumming …

“Suddenly shadowy figures entered his field of vision: they were there. Rubashov ceased to drum and stared. A second later they had passed … two dimly lit figures … in uniform … dragging between them a third, whom they hold under the arms. The middle figure hung slack and yet with a doll-like stiffness … stretched out at length, face turned to the ground … The legs trailed after, the shoes skated along on the toes … Whitish strands of hair hung over the face … Drops of sweat clung to it; out of the mouth spittle ran thinly down the chin … The moaning and whimpering gradually faded away, it came to him only as a distant echo, consisting of three plaintive vowels: ‘u-a-o.’ But before they had turned the corner … Bogrov bellowed out loudly twice, and this time Rubashov heard … the whole word … Ru-ba-shov.

“Then, as if at a signal, silence fell. The electric lamps were burning as usual, the corridor was empty as usual. Only in the wall No. 406 [the lunatic] was tapping: ARISE, YE WRETCHED OF THE EARTH.”

Archives

Tags

Adolf Berle Alexander Ulanovsky Alger Hiss Arthur Koestler Atlas Shrugged Ayn Rand Benn Steil Cold Friday Cold War Communism Dwight Eisenhower FDR George W. Bush Ghosts on the Roof Harry Dexter White Harry Truman Hiss Case House Un-American Activities Committee HUAC Ignatz Reiss John Loomis Sherman John Maynard Keynes Joseph McCarthy Joseph Stalin Karl Marx Leon Trotsky Max Bedacht Middle East National Review Peter the Great Pumpkin Papers Ralph de Toledano Richard Nixon Ronald Reagan Sputnik TIME magazine Tony Judt Vladimir Lenin Walter Krivitsky Westminster Whittaker Chambers William F. Buckley William F. Buckley Jr. Winston Churchill YaltaArt Resources

- B&W Photos from Farm Security Administration-Office of War Information Collection

- Life of the People: Radical Impulse + Capital and Labor

- Art of Marxism

- Comrades in Art

- Graphic Witness

- Jacob Burck

- Hugo Gellert + Gellert Papers

- William Gropper

- Jan Matulka: Thomas McCormick Gallery + Global Modernist

- Esther Shemitz Chambers

- Armory Show 1913

Pages from old website

Official website of Whittaker Chambers ( >> more )

Spycraft

- China Reporting

- CIA

- CIA – Alger Hiss Case

- Cold War Files

- Cold War Studies (Harvard)

- Comintern Online

- Comintern Online – LOC

- CWIHP – Wilson Center

- David Moore – Critical Thinking and Intelligence Analysis

- DC Writers: WC Home

- Economist – Espionage

- Essays on Espionage

- FBI – Rogue DNS Checker

- House – Hearing 08/25/1948

- House – Hiss Subpoena

- InfoRapid: WC

- Max Bedacht

- New York Times – Espionage

- NSA – FOIA Request

- PBS NOVA – Secrets Lies and Atomic Spies

- Richard Sorge

- Secrecy News

- Sherman Kent – Collected Essays

- Spy Museum – SPY Blog

- Thomas Sakmyster – J Peters

- Top Secret America – Map

- UK National Archives

- Vassiliev Notebooks

- Venona Decrypts

- Washington Decoded

- Washington Post – Espionage

- Zee Maps

Libraries

- American Commissar by Sandor Voros

- American Mercury – John Land

- American Writers Museum

- Archive.org – HUAC

- Archive.org – Lazar home

- Archive.org – Lazar Report

- Archives.org: 1948 – Hearings

- Archives.org: 1950 – Sherman Lieber

- Archives.org: 1951 – Sorge

- Archives.org: Ernie Lazar FOIA

- Archives.org: Ernie Lazar FOIA Collection

- Bio – Bennet Cerf

- Bio – Zara Witkin

- Bloomsburg University: Counterattack

- Bloomsburg University: Radical Publications

- Brooklyn Eagle 1948

- Centre des Archives communistes en Belgique

- CIA FOIA WC

- Daily Worker (various)

- Daily Worker: Marxists.org

- DC – Kudos

- DC – ORCID

- DC – ResearcherID

- DC – ResearchGate

- DC – SCOPUS

- Digital Public Library of America

- Erwin Marquit – Memoir

- FBI

- FBI Vault – WC

- Google: Books – WC

- GPO – WC

- GW – ER Papers: WC

- GWU: Eleanor Roosevelt WC

- Harvard College Writing Center – WC Summary

- Hathi: WC

- IISH: Marx Engels Papers

- ILGWU archives

- Images AP

- Images Corbis

- Images Getty Time Life

- Images LOC

- INKOMKA Comintern Archives

- International Newsletter of Communist Studies (Germany)

- JJC/CUNY – HC

- Labor Archives in the United States and Canada

- Life – WC

- LOC LCCN WC

- NBC Learn K-12: Spy Trials

- New Masses (Archive.org) 1926–1933

- New Masses (Marxists.org) 1926–1933

- New Masses (USussex) 1926–1938

- NSA: FOIA requests

- Ollie Atkins Photos

- Open Library: WC

- People: WC

- Poetry: Defeat in the Village

- PSA Communism

- SLU Law: HCase

- SSRN: Berresford – Hiss Case

- SUFL: Collections

- Tamiment: Collections

- Truman Library – John S. Service

- Truman Library – Oral Histories

- Truman Library – WC

- UCBerk * eBooks

- UCBerk: China – Edgar Snow

- UCBerk: China – Grace Service

- UCBerk: China – Kataoka

- UCBerk: China – Mackinnon

- UCBerk: China – Owen Lattimore

- UCBerk: China – Stross

- UCBerk: France – Revolution

- UCBerk: Russia – Bread 1914-1921

- UCBerk: Russia – Comintern

- UCBerk: US – Conservatism WC

- UCBerk: US – Hollywood Weimar

- UCBerk: US – James Joyce

- UCBerk: US – Lawyers

- UCBerk: US – NY Intellectual

- UCBerk: US – Waterfronts

- UCLA Library Film & TV Archive

- UK National Archives: WC

- UMich: Salant Deception

- UPenn: US – Left Ephemera Collection

- UPitt: US – Harry Gannes

- USDOE

- USDoED

- USDOJ

- USDOS

- Wall St + Bolshevik Revolution – Anthony Sutton

- Wikipedia A-D

- WikiSearch WC

- WordPress themes – Anders Noren

- x FSearch – WC