- Articles

- Commonweal

- TIME – Reviews

- TIME – Articles

- TIME – Cover Stories

- TIME – Foreign News

- Life Magazine

- Harper’s: A Chain is as Strong as its Most Confused Link

- TIME – Religion

- New York Tribune

- TIME

- National Review

- Soviet Strategy in the Middle East

- The Coming Struggle for Outer Space

- The Left Understands the Left

- To Temporize Is Death

- Big Sister Is Watching You

- Springhead to Springhead

- Some Untimely Jottings

- RIP: Virginia Freedom

- A Reminder

- A Republican Looks At His Vote

- Some Westminster Notes

- Missiles, Brains and Mind

- The Hissiad: A Correction

- Foot in the Door

- Books

- Poetry

- Video

- About

- Disclaimer

- Case

- Articles on the Case

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1948

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1949

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1950

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1951

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1952

- Trial by Typewriter

- I Was the Witness

- The Time News Quiz

- Another Witness

- Question of Security

- Fusilier

- Publican & Pharisee

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Kudos

- Letters – June 16, 1952

- Readable

- Letters – June 23, 1952

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Nominee for Veep

- Recent and Readable

- Recent and Readable

- Democratic Nominee for President

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Fighting Quaker

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Timely Saints

- Nixon on Communism

- People

- Who’s for Whom

- 1952 Bestsellers

- Letters – December 15, 1952

- Year in Books

- Man of Bretton Woods

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1953

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1954

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1955

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1956-1957

- Private

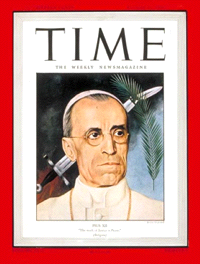

Religion: Peace & the Papacy

Monday, Aug. 16, 1943

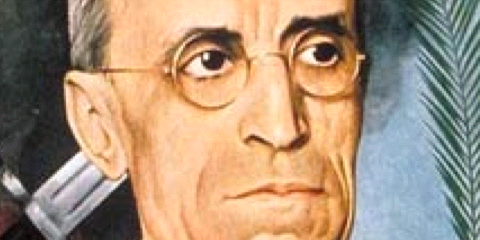

Religion: Peace & the Papacy

(See Cover)

Dismayed by the horrors of a war which is bringing ruin to peoples and nations, we turn, O Jesus, to Thy most loving Heart as to our last hope, O God of Mercy, with tears we invoke Thee to end this fearful scourge; O King of Peace, we humbly implore the peace for which we long … Pity the countless mothers in anguish for the fate of their sons; pity the numberless families now bereaved of their fathers; pity Europe, over which broods such havoc and disaster. Do Thou inspire rulers and peoples with counsels of meekness; do Thou heal the discords that tear the nations asunder; Thou Who didst shed Thy Precious Blood that they might live as brothers, bring men together once more in loving harmony. And as once before to the cry of the Apostle Peter: “Save us, Lord, we perish …”

— Benedict XV‘s Special Prayer for Peace

The beginning of wisdom about the Pope is to know that whatever else he may be doing he is always for peace. Peace rumors all over Europe last week (see p. 23) might or might not be well founded. But there was no doubt that Pius XII was busily trying to act as grand pacificator.

Catholics would understand his position and his motives at once.

Non-Catholics might find it hard to draw the line between the Pope’s diplomatic and his apostolic roles.

The world had again to take stock of this centuries-old force, the Roman Catholic Church. Who is this apostle of peace? What is Pope Pius XII as symbol, as man, as churchman, as a power for peace among nations and the more fundamental social peace?

Symbol of a Symbol. To devout Catholics, the Catholic Church is more than an institution: it is a symbol of eternity. And the Pope, from the moment of his papal elevation, is more than a man: he is a symbol of the symbol of eternity. As symbol, Pius XII is:

- His Holiness the Pope, Bishop of Rome and Vicar of Jesus Christ, Successor of St. Peter, Prince of the Apostles, Supreme Pontiff of the Universal Church, Patriarch of the West, Primate of Italy, Archbishop and Metropolitan of the Roman Province, Sovereign of Vatican City, Servant of the Servants of God.

- Representative of the Church Triumphant (which is in Heaven), of the Church Suffering (which is in Purgatory), of the Church Militant (which is on earth).

- Absolute spiritual ruler of a hierarchy which includes 47 cardinals, 13 patriarchs, some 2,000 archbishops and bishops and about 300,000 priests.

- Absolute spiritual sovereign of some 365,000,000 Roman Catholics throughout the world.

- Infallible formulator for them of dogma in faith and morals.

- Pontiff No. 262 in a prelatical line which includes the Apostle Peter (whom, Catholics believe, Christ commanded to establish the Roman Catholic Church); Leo the Great (who saved Rome from Attila’s sacking Huns); Lucius III (who instigated the Inquisition); Innocent III (who exercised effective political control over all Italy and much of Europe, bringing the temporal power of the Papacy to its high-water mark); Leo X (a worldly, cultivated gentleman who excommunicated Martin Luther and proved incapable of dealing with the problems of the Reformation); Alexander VI (a Borgia, who practiced simony and nepotism and failed in his master plan to conquer and unify Italy); Pius VII (whose Concordat with Napoleon restored Catholicism to France); Leo XIII (whose encyclical, Rerum Novarum, first diagnosed for Catholics the sickness of contemporary society and called upon them authoritatively to cure it).

As symbol Pius XII is a spiritual autocrat of incalculable power.

The Man. But despite the massiveness of the symbol, the Pope is also supremely important as a man. For as Pope (when he speaks ex cathedra), he is infallible. But as a man, he is fallible like any other. And this fallibility determines his place among the “good” Popes or the “bad” Popes, and hence his influence upon history.

For the same reason, Popes’ lives are written chiefly after their deaths. The biography of a living Pope is officially meager. Pius XII is no exception. But his biographical skeleton is important for the context of history it reveals.

Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli, who today is one of the world’s most hardheaded statesmen, was born in 1876 — five years after Bismarck founded the Second Reich; six years after Italy achieved unification by Vittorio Emanuele II‘s seizing Rome from the Papacy, and Pope Pius IX immured himself in his last possession as “the prisoner of the Vatican”; five years after the Paris proletariat bloodily introduced Europe to a new form of the state—the commune or soviet. The consequences of these events were to mark the highlights of the career of Eugenio Pacelli and of the world.

Both Eugenio Pacelli’s grandfathers were Vatican functionaries. His father was dean of the Vatican law corps. Young Pacelli practically grew up in church. As a boy he played in the piazza of Rome’s Santa Maria della Pace, from whose wall he took his personal motto: Opus justitiae pax (The work of justice is peace).

In 1899 Pacelli was ordained a priest. Almost at once Monsignor Gasparri, later papal Secretary of State and Pius XI’s grey eminence, invited Pacelli to stop teaching law at the Roman Seminary of Apollinare and to help him make history in the Congregation for Extraordinary Ecclesiastical Affairs (the Vatican’s foreign relations office). Pacelli continued there and in the Secretariat of State until he became Pope in 1939. Nevertheless, he saw more of the Church Universal than any other prelate in papal history.

In 1917 (the Russian Revolution had just begun) Pacelli went as Papal Nuncio to Munich, tried (and failed) to talk the Kaiser into a peaceful frame of mind After the Kaiser fled, Pacelli lived through the Bavarian Soviet Republic. On one occasion he faced down a band of armed revolutionaries who had broken into the Papal Embassy, intending to loot the building.

In 1925, Archbishop Pacelli 1 concluded a Concordat with Bavaria. Franz Ritter von Epp’s forces had overthrown the Soviet, and a police spy named Adolf Hitler was scooping in revolutionary circles for the new government.

In 1929 Pacelli negotiated a Concordat with social-democratic Prussia. When Lutherans objected, Pacelli suggested calling the Concordat a “solemn convention.” Everybody was pleased.

In 1929 Pacelli was called to Rome, made a Cardinal and two months later Vatican Secretary of State—the official of whom Sixtus V once wrote: “He must know everything, understand everything —but he must say nothing.”

In 1936, he sailed to North America, visited Manhattan’s Empire State Building, the Liberty Bell, Mount Vernon, innumerable U.S. Catholic hierarchs. He also traveled 8,000 miles by plane and lunched with the Franklin Roosevelts at Hyde Park. Said Pacelli: “I enjoyed lunching with a typical American family.” This trip was an eyeopener to American travelers who saw the statesman of the church riding in a plane break out his portable typewriter and vigorously go to work in midair.

Other trips took Pacelli to Hungary, Switzerland, France, South America.

But Pacelli did not neglect Vatican City. About the time that Pius XI appointed Pacelli Prefect of the Reverend Fabric of St. Peter’s (guardian of Vatican buildings), Mussolini banned the Catholic Boy Scouts and started to wipe out Catholic Action in Italy. The Pope wrote an encyclical (Non abbiamo bisogno) attacking the Fascist action, but since the Fascists controlled all the telegraph lines and cables to the outside world, Mussolini was in a position to read and reply to the encyclical before the world read it.

Cardinal Pacelli got out of this dilemma by having his great friend, Monsignor (now New York’s Archbishop) Francis Spellman, hustle copies of the encyclical to France by plane. But the incident made a deep impression on Pacelli. Soon he had equipped the Vatican with a short-wave radio station (“for research and propaganda”), a new electric powerhouse, a fleet of modern automobiles (gifts of the manufacturers) to replace the old carriages, electric elevators, 800 telephones (the Pope’s telephone is solid gold stamped with the Papal Arms and the trade-mark of International Telephone & Telegraph Co.), a telephoto apparatus, an electric device to replace the bell ringers at St. Peter’s. “The fabric of St. Peter’s,” said a Catholic commentator, “became as modern as the fabric of New York.”

In 1939 Cardinal Pacelli came face to face with the event which was to climax his ecclesiastical career. Pope Pius XI died. From all points of the compass Cardinals rushed to Rome to elect his successor. Cardinal Pacelli personally wired the Italian Line to ask that the Neptunia make an extra fast trip so that the Latin American Cardinals would arrive for the voting. In his haste one Cardinal was compelled to fly from Portugal over the battle lines of the Spanish Civil War. For the first time in history U.S. Cardinals also were present at the conclave to elect a Pope.

Cardinal Pacelli was chosen Pope on the third ballot. No Pope had been chosen so quickly since 1623. Pacelli was the first Papal Secretary of State to become Pope since 1775. He was elected on his 63rd birthday. Said one Cardinal, who watched Pacelli while the votes were being counted : “I have never seen anyone look so pale and yet continue breathing.”

Papal Politician. Cardinal Pacelli’s pre-pontifical travels were facilitated by the fact that he talks fluently in eight languages. What he talks about in them, and whom he talks to, would constitute a key-to the most sinuous and controversial politics pursued by any world power — the Church Temporal’s diplomacy. It would also constitute a cryptogram of current history.

“Politics,” said Cardinal Manning, “is a part of morals.” It was a part of morals that has dogged Pacelli even on his most apostolic and least political missions, even when he was gently (but sure-handedly) weaving the diplomacy of the Church Militant in the reverent hush of the Secretariat of State. Whether the morals of Pacelli’s diplomacy were good or bad morals is a violently debated issue.

Of those who believe them to be bad (radicals of all brands, most anti-Catho lics, many non-Catholics and even some Catholics), almost none can prove his point because none but the Vatican knows all the facts and circumstances. In general the most serious charges against the Church concern the skill with which the Vatican and its hierarchs have fished and swum in the Fascist sea surrounding them. Vatican critics of various sorts point to various specific chapters of Pacelli diplomacy:

- The Vatican’s support of General Franco during and after the Spanish Civil War.

- The pro-Fascist sentiments of some Catholic prelates.

- The Lateran pacts and Concordat with Mussolini whereby the Italian Government agreed to pay the Vatican $39,200,000 in cash; to give it $52,300,000 worth of Ital ian Government bonds; to recognize Vatican City as a sovereign state; and to make Catholicism the state religion of Italy.

- The 1933 Concordat with Hitler “in spite of many serious misgivings.”

- The Vatican’s haste to embrace Marshal Pétain and Vichy.

- The Vatican policy toward Russia, which pleases scarcely anybody. The papacy’s unflagging crusade against Communism in & out of Russia has long infuriated Leftists. Its recent broadcasts to Russia in Russian have worried: 1) radicals, who fear Catholic propaganda; 2) conservatives, who wonder what the Vatican is up to now.

People who believe that Vatican politics are good morals (and these include most Catholics and a scattering of non-Catholics) defend papal diplomacy with pleas of necessity, adaptability, the ancient wisdom of the Church, and the long view, which in the case of Catholicism embraces eternity — a perspective so vast that differences between democracy and dictator ship sometimes blur to the ecclesiastical eye.

Vatican apologists also like to point to the fact that if Catholic-Fascist relations have been warm in the case of Spain, tolarable in the case of Italy, bearable in the case of Germany, Vatican relations with the democracies have been downright friendly.

But no matter what critics might say, it is scarcely deniable that the Church Apostolic, through the encyclicals and other papal pronouncements, has been fighting against totalitarianism more knowingly, devoutly and authoritatively, and for a longer time, than any other organized power.

The Work of Justice. As a power for peace, Pius XII is less a man than the continuation .of a policy. But what the Catholic peace policy is, non-Catholics sometimes find it difficult to discover. And even Catholics find it hard to put the Church’s peace program in a nut shell.

Enunciation of the Catholic peace poli cy is chiefly the work of the last five Popes (Leo XIII, Pius X, Benedict XV, Pius XI, Pius XII). It is at once the most diffuse and most fundamental of peace programs because it is based on the belief that wars between nations can never be prevented until class conflicts within na tions have been adjusted. Therefore it talks less about peace than about the causes of social war — Capital and Labor, the relations between the individual and the State, Communism, the position of the family, regimentation, materialism, etc.

Men often glibly say that World War II is a social revolution. But the Catholic Church is the only Christian power that has systematically studied the problem from this viewpoint, or taken steps to end class war by compromising the struggle between Capital and Labor. What the papacy demands is social justice within nations. It believes that if this can be accomplished, wars will largely cease: the work of justice is peace. Instead of Karl Marx’s violent “revolutionary reconstitution of society as a whole,” the Catholic Church wants a conservative reconstitution of society in the name of God, justice, peace. Moreover, it insists on the dignity of the individual whom God created in his own image and for a decade has vigorously protested against the cruel persecution of the Jews as a violation of God’s Tabernacle.

The Church’s great human hope is embodied in a series of papal encyclicals of which the two most fundamental are Rerum Novarum (May 15, 1891) and Quadragesima Anno (May 15, 1931). Not long after Eugenio Pacelli was born, Leo XIII looked beyond the Vatican and saw European civilization sick in body from social septicemia and sick at heart from the standing threat of war. In Rerum Novarum Leo put a fearless finger on the morbid core of Europe’s social sickness. He attacked the misery of Europe’s impoverished masses and those responsible for their condition.

Forty years later (the Church moves deliberately under the aspect of eternity) Pius XI affirmed his predecessor’s policy in the encyclical Quadragesima Anno. He pointed to the growing danger of “atheistic Communism” and Socialism. He also criticized capitalism for its religious and human indifference to the conditions of the workers and for the way in which more & more power was concentrated in the hands of fewer and fewer capitalists. Liberalism 2 the Pope called “the father of Socialism” and declared that its “heir” is Bolshevism; for, like Communists, most Catholics regard liberals as people who would be Communists if they had the courage or the understanding to see the implications of the liberal position.

The Basis of Peace. These encyclicals laid the basis for the Church’s peace pro gram. But no Pope has summarized more forcefully than Pius XII the Church’s position on the social issues upon which peace depends. In a soth anniversary broadcast of Rerum Novarum (June 1, 1941), Pius XII brought that position up to date in a series of powerful assertions:

- On the Role of the Church: “It is … the indisputable competence of the Church to decide whether the bases of a given social system are in accord with the unchangeable order” of God.

- On the Rights of the Individual: The power of the State “does not imply a pow er so extensive over the members of the community that in virtue of it the public authority can interfere with the evolution of that individual … decide on the beginning or … the ending of human life, determine … his physical, spiritual, religious and moral movements.” This would mean “falling into the error that the proper scope of man on earth is society, that society is an end in itself.”

- On Labor: “The duty and right to organize the labor of the people belongs above all to the people immediately interested: the employers and the workers … Every legitimate and beneficial interference of the State in the field of labor should be such as to safeguard and respect its personal character.

- On the Distribution of Goods: “The goods which were created by God for all men should flow equally to all according to the principles of justice and charity.”

- On the Family: “In the family the nation finds the natural and fecund roots of its greatness and power … A so-called civil progress would … be unnatural which — either through the excessive burdens imposed, or through exaggerated direct interference — were to render private property void of significance, practically taking from the family and its head the freedom to follow the scope set by God for the perfection of family life.”

- On the Land: “As a rule, only that stability which is rooted in one’s own holding, makes of the family the most vital and most perfect and fecund cell of society.” Equally emphatic was Pius XII in his 1942 Christmas broadcast:

Against Regimentation: A Christian “should cooperate … in giving back to the human person the dignity given to it by God … should oppose the excessive herding of men, as if they were a mass without a soul…”

- On the Dignity of Work : A Christian “should give to work the place assigned to it by God from the beginning. As an indispensable means toward gaining over the world that mastery which God wishes for His glory, all work has an inherent dignity and at the same time a close connection with the perfection of the person. The Church does not hesitate to draw the practical conclusions which are derived from the moral nobility of work…

- Against Legal Instability: A Christian “should collaborate toward a complete rehabilitation of the juridical order. The juridic sense of today is often altered and overturned… The cure for this situation becomes feasible when we awaken again the consciousness of a juridical order resting on the supreme dominion of God, and safeguard from all human whims…”

- On the State: A Christian “should help to restore the State and its power to the service of human society, to the full recognition of the respect due to the human person and his efforts to attain his eternal destiny.

Nobody knows yet whether Pius XII will be invited to the peace conference that follows World War II or whether he would accept if he were invited. Benedict XV was expressly barred from Versailles by a clause in the secret treaty of London. But whether or not the Pope is present, the influence of the Catholic Church’s peace policy will be tremendous. Most Catholics and non-Catholics alike would agree that a peace that does not embody, at least roughly, the papal position on fundamental social issues will bring not social peace but a sword. For when traditional justice fails, retributive justice supervenes. Failure to grasp this fact means failure to understand the words that Dante read above the gates of Hell:

Giustizia mosse il mio alto Fattore; fecemi la divina Potestate, la somma Sapienza e il primo Amore …Lasciate ogni speranza qui voi ch’en-trate. 3

Notes:

- Eight years earlier Benedict XV had made Pacelli Titular Archbishop of Sardes (an ancient See in Asia Minor) — Note from TIME magazine – Editor ↩

- Walter Lippmann and a pious churchman might agree that Leo XIII was attacking not liberalism as defined by Lippmann in The Good Society, but the common perversion of liberalism. — Note from TIME magazine – Editor ↩

- Justice moved my great Maker; Divine Power made me, and supreme Wisdom and primal Love … All hope abandon, ye who enter here. ↩

Archives

Tags

Adolf Berle Alexander Ulanovsky Alger Hiss Arthur Koestler Atlas Shrugged Ayn Rand Benn Steil Cold Friday Cold War Communism Dwight Eisenhower FDR George W. Bush Ghosts on the Roof Harry Dexter White Harry Truman Hiss Case House Un-American Activities Committee HUAC Ignatz Reiss John Loomis Sherman John Maynard Keynes Joseph McCarthy Joseph Stalin Karl Marx Leon Trotsky Max Bedacht Middle East National Review Peter the Great Pumpkin Papers Ralph de Toledano Richard Nixon Ronald Reagan Sputnik TIME magazine Tony Judt Vladimir Lenin Walter Krivitsky Westminster Whittaker Chambers William F. Buckley William F. Buckley Jr. Winston Churchill YaltaArt Resources

- B&W Photos from Farm Security Administration-Office of War Information Collection

- Life of the People: Radical Impulse + Capital and Labor

- Art of Marxism

- Comrades in Art

- Graphic Witness

- Jacob Burck

- Hugo Gellert + Gellert Papers

- William Gropper

- Jan Matulka: Thomas McCormick Gallery + Global Modernist

- Esther Shemitz Chambers

- Armory Show 1913

Pages from old website

Official website of Whittaker Chambers ( >> more )

Spycraft

- China Reporting

- CIA

- CIA – Alger Hiss Case

- Cold War Files

- Cold War Studies (Harvard)

- Comintern Online

- Comintern Online – LOC

- CWIHP – Wilson Center

- David Moore – Critical Thinking and Intelligence Analysis

- DC Writers: WC Home

- Economist – Espionage

- Essays on Espionage

- FBI – Rogue DNS Checker

- House – Hearing 08/25/1948

- House – Hiss Subpoena

- InfoRapid: WC

- Max Bedacht

- New York Times – Espionage

- NSA – FOIA Request

- PBS NOVA – Secrets Lies and Atomic Spies

- Richard Sorge

- Secrecy News

- Sherman Kent – Collected Essays

- Spy Museum – SPY Blog

- Thomas Sakmyster – J Peters

- Top Secret America – Map

- UK National Archives

- Vassiliev Notebooks

- Venona Decrypts

- Washington Decoded

- Washington Post – Espionage

- Zee Maps

Libraries

- American Commissar by Sandor Voros

- American Mercury – John Land

- American Writers Museum

- Archive.org – HUAC

- Archive.org – Lazar home

- Archive.org – Lazar Report

- Archives.org: 1948 – Hearings

- Archives.org: 1950 – Sherman Lieber

- Archives.org: 1951 – Sorge

- Archives.org: Ernie Lazar FOIA

- Archives.org: Ernie Lazar FOIA Collection

- Bio – Bennet Cerf

- Bio – Zara Witkin

- Bloomsburg University: Counterattack

- Bloomsburg University: Radical Publications

- Brooklyn Eagle 1948

- Centre des Archives communistes en Belgique

- CIA FOIA WC

- Daily Worker (various)

- Daily Worker: Marxists.org

- DC – Kudos

- DC – ORCID

- DC – ResearcherID

- DC – ResearchGate

- DC – SCOPUS

- Digital Public Library of America

- Erwin Marquit – Memoir

- FBI

- FBI Vault – WC

- Google: Books – WC

- GPO – WC

- GW – ER Papers: WC

- GWU: Eleanor Roosevelt WC

- Harvard College Writing Center – WC Summary

- Hathi: WC

- IISH: Marx Engels Papers

- ILGWU archives

- Images AP

- Images Corbis

- Images Getty Time Life

- Images LOC

- INKOMKA Comintern Archives

- International Newsletter of Communist Studies (Germany)

- JJC/CUNY – HC

- Labor Archives in the United States and Canada

- Life – WC

- LOC LCCN WC

- NBC Learn K-12: Spy Trials

- New Masses (Archive.org) 1926–1933

- New Masses (Marxists.org) 1926–1933

- New Masses (USussex) 1926–1938

- NSA: FOIA requests

- Ollie Atkins Photos

- Open Library: WC

- People: WC

- Poetry: Defeat in the Village

- PSA Communism

- SLU Law: HCase

- SSRN: Berresford – Hiss Case

- SUFL: Collections

- Tamiment: Collections

- Truman Library – John S. Service

- Truman Library – Oral Histories

- Truman Library – WC

- UCBerk * eBooks

- UCBerk: China – Edgar Snow

- UCBerk: China – Grace Service

- UCBerk: China – Kataoka

- UCBerk: China – Mackinnon

- UCBerk: China – Owen Lattimore

- UCBerk: China – Stross

- UCBerk: France – Revolution

- UCBerk: Russia – Bread 1914-1921

- UCBerk: Russia – Comintern

- UCBerk: US – Conservatism WC

- UCBerk: US – Hollywood Weimar

- UCBerk: US – James Joyce

- UCBerk: US – Lawyers

- UCBerk: US – NY Intellectual

- UCBerk: US – Waterfronts

- UCLA Library Film & TV Archive

- UK National Archives: WC

- UMich: Salant Deception

- UPenn: US – Left Ephemera Collection

- UPitt: US – Harry Gannes

- USDOE

- USDoED

- USDOJ

- USDOS

- Wall St + Bolshevik Revolution – Anthony Sutton

- Wikipedia A-D

- WikiSearch WC

- WordPress themes – Anders Noren

- x FSearch – WC