- Articles

- Commonweal

- TIME – Reviews

- TIME – Articles

- TIME – Cover Stories

- TIME – Foreign News

- Life Magazine

- Harper’s: A Chain is as Strong as its Most Confused Link

- TIME – Religion

- New York Tribune

- TIME

- National Review

- Soviet Strategy in the Middle East

- The Coming Struggle for Outer Space

- The Left Understands the Left

- To Temporize Is Death

- Big Sister Is Watching You

- Springhead to Springhead

- Some Untimely Jottings

- RIP: Virginia Freedom

- A Reminder

- A Republican Looks At His Vote

- Some Westminster Notes

- Missiles, Brains and Mind

- The Hissiad: A Correction

- Foot in the Door

- Books

- Poetry

- Video

- About

- Disclaimer

- Case

- Articles on the Case

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1948

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1949

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1950

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1951

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1952

- Trial by Typewriter

- I Was the Witness

- The Time News Quiz

- Another Witness

- Question of Security

- Fusilier

- Publican & Pharisee

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Kudos

- Letters – June 16, 1952

- Readable

- Letters – June 23, 1952

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Nominee for Veep

- Recent and Readable

- Recent and Readable

- Democratic Nominee for President

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Fighting Quaker

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Timely Saints

- Nixon on Communism

- People

- Who’s for Whom

- 1952 Bestsellers

- Letters – December 15, 1952

- Year in Books

- Man of Bretton Woods

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1953

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1954

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1955

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1956-1957

- Private

Foot in the Door

Foot in the Door

National Review – June 20, 1959

By Whittaker Chambers

The googols are coming, and against them the College Door is Closing. A student who has Done It Himself suggests: Put Aeschylus in orbit

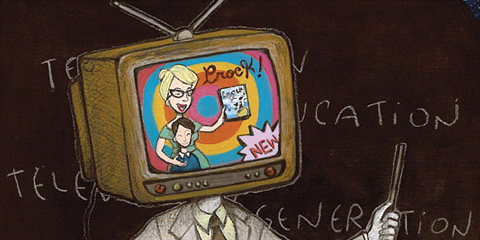

It looks to me as if The George Washington University (in Washington, D.C.) were helping to pioneer something whose long-range implications may be pretty important for a lot of us. What it implies, if I am right about it, is the beginning of the breakthrough in mass education, by using television. Of course, other institutions have been experimenting with television education, and on a grander scale. But George Washington’s project happens to be the one that I have seen close up; so I shall limit myself to it. The larger significance of this development seems scarcely possible to overrate. Among other mercies, if time and a fuller curriculum justify the general use of TV for teaching, that would seem to thrust a formidable foot into the Closing College Door.

By now, there cannot be many of us who are unfamiliar with that implacably Closing Door. Daily, and sometimes several times a day, it has been threatening to slam in our faces, or our children’s or grandchildren’s. The problem posed by the Closing College Door is due not only to our population explosion, but to the realization, abruptly brought home by those sky-writing Sputniks, etc., that: 1) a lot more Americans are going to have to be educated a lot better and more quickly than in the past; and that 2) henceforth education bears directly on national security and possibly national survival. On the TV screen, we see a flutter of black and white flakes, rather like snow mixed with soot. This is radioactive fallout; and, any day now, an accompanying voice tells us, we may find ourselves in the midst of it. The voice is unruffled, almost cosy — nil desperandum Teucro duce et auspice Teucro — as if you and I or the commentator were the kind of people who would ever let ourselves show surprise at a little radioactive fallout.

Behold the contrast with the Closing College Door. Nothing lulling about this one. The accompanying voice is that of the Education Lobby. The scene on the TV screen is full of pathos, too. We see Willie, gowned in his high school graduation togs, clutching his diploma, all set for the next step: going to College. Heartbreak: Willie isn’t going anywhere, except that he is fated to go forever un-higher-educated. For — a Delphic voice warns us — by 1984 (or whatever the fateful deadline is) the Closing College Door will have slammed shut in Willie’s eager face. Googols of secondary school graduates will be besieging the gates of campuses, quite futilely, since college facilities will be totally inadequate to cope with such hordes. (In case you do not yet realize what age you have been born into, a googol is shorthand for a digit followed by one hundred zeros.) We are invited to write for a leaflet, setting forth these matters more fully, from an address sufficiently pseudonymous to stir a surmise that this is an air-hole of the Education Lobby, or one of its isotopes.

Our Own Dollars

The problem of the Closing College Door is beyond question a real one. And it would be impermissible to treat Willie and his plight so lightly, if this particular presentation of it did not remind us uneasily of the commercials which try to persuade us that virility is inseparable from smoking certain brands of cigarettes. In each case, we resent a sneak assault on good sense. In Willie’s case, it takes no great wits to guess what we are expected to do next: shake out what is left in our lank wallets while we pressure our legislators (themselves, paradoxically, not always beacons of literacy) to syphon federal taxes into higher education. Parents are not, apparently, presumed to be educated (or natively bright) enough to perceive that federal aid to education is their own tax-ravaged and inflated dollars fed into academic tills by other-directed and coercive means.

Perhaps it will come to this. But let us not delude ourselves about what it is we shall have come to. This is the age of euphemism, because this is the age of the Total State that is dawning, more or less everywhere, though under various softening and dissembling names and forms, on various impressive pretexts or necessities. But it is not deemed expedient that we should grasp what age it really is — at least, not all at once, or all of us at once. So, perhaps, of necessity, the State must soon be into the Business of Education, as the witty and bracingly arrogant Professor J. K. Galbraith assured us, only the other day, that it must.

…and Gladly Paid

But must it? It is just here that that formidable foot I mentioned may have got into the Closing College Door. Which brings us back to The George Washington University and its television project. Early this year, the University’s College of Special Studies, in cooperation with Station WTOP (the Washington Post), offered a TV course in Russian for beginners. Within a fortnight or so, some 3,400 students had paid their fees (up to $75), and enrolled for the course. Perhaps it is worth remembering that Russian (like English) is one of the most difficult of the great cultural languages; and that, until recently, those who struggled with it had to rise before daybreak for the lectures which go on the air at 6:30 a.m. That invisibly listening 3,400 must form one of the biggest classrooms anywhere. They equal the entire population of many a college campus. Bear in mind, too, that they are being taught by a single instructor — the very competent Mr. Vladimir Tolstoy. One mind efficiently instructing a formally enrolled class of 3,400 other minds — it is at that point that the possibilities of television education begin to open out. When this is possible and comparatively simple, why need the Closing College Door close, or be held open chiefly by the strong-arm State? Why cannot a comparatively small faculty (and a highly select one at that) instruct millions just as well as 3,400?

The Education Lobby

I am not an educator, so that the reasons why not do not leap to my mind as fleetly as I have no doubt they will leap to authoritative minds. Some of the objections must certainly be well taken, if only on grounds of ca ‘ canny. Some, we may feel reasonably sure, will be simple obstruction, not perhaps consciously identified as such by the obstructors. For here we run up against the rooted human reluctance to innovation (a reluctance for which, at times, there is something to be said), but which, perhaps rather more often, amounts to a dense inertia. We also get into the preserves of vested academic interest. And I incline to the view that Fafnir, grunting and belching over the Niebelung Hoard, was a tame and temperate dragon compared to schoolmen, guarding academic interests to which they have staked claims during dedicated lifetimes, with little enough recognition, and few of this world’s rewards.

Here, too, we can only brush the powerful forces, which we lump loosely as the Education Lobby, and which appear, in general, to be bound by the most tender, consanguine ties to vaster, more powerful forces that look to the State as the sovereign solvent of our social (and most other) problems. And this, not because such heads are peculiarly mischievous, wicked or (as an otherwise intelligent Conservative said to me recently) “immoral.” Mischief and malignity might be comparatively easy to deal with. But these folk are, in general, intelligent, articulate, and intellectually effective, to the degree in which, having looked into the problem and sounded its complexities in depth, they find no agency but the State adequate to solving it on such a scale. It is this, precisely, that gives them a quite unbearable moral presumption. They also note that, given the general pattern of the age, the whole momentum of historical forces, quite apart from what anybody might want to do, or not to do, about it, is working to strengthen the State. And their sense of riding this irresistible momentum is precisely what gives them an insufferable self-righteousness. Since anything that magnifies the power of the State hastens a process, which is deemed inevitable, whatever tends to speed it up shortens it, and is, to that degree, beneficent. Anything that slows it down is unintelligent, maleficent, and, in such terms, “immoral.” That is to say, much the same judgment reached by my Conservative friend, but reached from the other direction by reading the same terms in a reverse sense.

Since the Closing College Door tends to strengthen the State, that Door is a godsend to such folk, and they may be expected to put their full and ululant weight behind it, and against anything that might keep it ajar. They do not necessarily think of it this way. But we are not speaking here about what individual heads think, but about relationships of forces and interests, and what happens when individual men are drawn by them into action, which has a way of depersonalizing most of us. In any event, if televised education really threatens to thrust a foot in the Closing College Door, we may well see some plain and fancy surgery to sever the foot at the ankle.

Lines of Attack

One line of surgery seems obvious. While talking with the head of the Slavic Department and others at George Washington, I thought I caught the whine of the whetstone just behind their backs. The same sound seemed phrased in a question on the form that many TV students filled out for the College of Special Studies: “Can Education be successfully given over TV?” My answer: “No question whatever about it; it can.”

Another line of attack is easily foreseen. Presumably, it would go much like this. Suppose you are televising not just a single course; and one, too, about which there is, admittedly, a touch of fad. Suppose you are televising a full semester’s high school or college work, especially to younger students. When they are put on their own, largely removed from the hourly discipline of class attendance and supervision, what grounds have you for expecting, what right have you to expect, that the mass of such students would do the necessary work? My reaction to that one is brief, blunt, and to many, I should think, abhorrent: about this the Russians seem to me unquestionably right. Those who cannot learn should be spared the ordeal. Those who will not learn should be spared the privilege. If they will not learn, and, while learning, keep to a certain standard of progress — into the factories with them, or stores, or any occupation that will usefully employ (and train) their hands and heads, without making undue demands upon their minds. At the same time, every effort should be made to help out of routine, stultifying jobs young (and older) people who can, and will, use their minds, but are prevented from learning by the need to earn. No use to say that this is undemocratic. This selective process, and only this one, is truly democratic, drawing out of the fecund, unranked body of the nation, the forces on which, when trained, depends the well-being of the community as a whole.

In the past, our slackness about learning did not matter. At least, it did not matter enough to justify so drastic a stand. But the past and its easy ways (which I, personally, prefer to anything that is likely to take their place) helps us little or nothing now. We are visibly on a historical turning-point which is all but certain to determine the human condition for an unforeseeable reach of time. How that turning-point comes out for us, turns, in a much more foreseeable degree, on what the oncoming generations make of their minds. And not only the oncoming generations. There are plenty of adult minds (a sizable arsenal of them, one suspects) whose efficiency a little easily accessible education would greatly step up, probably to their own considerable exhilaration.

TV Screen and Campus

I am not suggesting, of course, that televised education can replace (or displace) Harvard — letting that name stand, in excelsis, for many others. No merely functional teaching is likely to be a substitute for a campus education with its celebrated intangibles, dedicated to shaping, as we are reminded at almost any Commencement exercises, “the whole man.” There is also a fairly dreary waste (which also has its justifying arguments) in any college education. Ninety windows smashed in one fraternity house in one glorious night (to cite an item of rather recent personal recollection) scarcely seem indispensable to shaping “the whole man.” Nor is all the waste on the side of the students, as anybody knows who has been exposed to the enshrined prejudices, posturings and crotchets of certain old faculty boys of nostalgic memory. These, too, have their justifications, though one cannot help wondering how those antics might go over on a TV screen under the sobering stare of millions.

I am not suggesting, either, that televised education is coming tomorrow, or that it does not pose its own order of grave and complex problems; or that it is a cure-all for our educational plight. I am saying only that the need is great, pressing, and generally conceded; that, in television, a means to meet the need, at least in part, appears to be at hand; that it is comparatively inexpensive and need not involve the State. What is required next would seem to be the will to mate the means and the need; to work out organizational and other problems, which, however difficult, are likely to be somewhat less so than those of splitting the atom or orbiting a rocket around the sun. I venture that, if need and means were brought together, the public response might be at least as startling as the response to The George Washington University’s Russian course.

In fact, the problem’s thrust outstrips all such terms. It is clear that mankind may, within a rather short time, blow itself into a poisonous powder and lie dusting a vaster putrefaction. I happen to believe that the odds, though touch and go, are rather against apocalypse. If this proves true, it seems to me that, for a century or so, the energies of mankind will be increasingly directed to, and absorbed, with an exclusive and unparalleled intensity, in raising the level of human material well-being, i.e., social wealth, and in solving certain related problems. One of the beneficent side-effects of the crisis of the twentieth century as a whole, is a dawning realization, not so much that the mass of mankind is degradingly poor, as that there will be no peace for the islands of relative plenty until the continents of proliferating poverty have been lifted to something like the general material level of the islanders. It is this perfectly practical challenge, abetted by a sound self-interest, which must engross the energies of mankind, and more and more, perhaps, inspire it as a perfectly realizable vision. Especially, I should think, it would inspire Americans, who, in a sense, invented abundance; and who appear to feel what other nations have felt as a sense of destiny, only in the generous act of bringing their abundance, and the know-how behind it, to less fortunate breeds.

But the world is also degradingly ignorant — and by no means only in Africa. Unless the general level of mind is raised at the same time as the level of material well-being, and not too many steps behind, we shall all risk resembling those savages whom, within living memory, civilizers introduced to the splendor of top hats and tight shoes, for the greater glory of their extremities, leaving unredeemed the loin-cloth of their middle zones, and the wits between their ears.

In the Next Century

In fact, we shall have little choice but to raise the level. A modern economy of abundance cannot be sustained, cannot even be organized, without also organizing (i.e., educating) the brains to run it. At the point where such brains must number millions, education must almost certainly take to the air. It seems extremely doubtful that the old local centers of learning, however expanded, can cope with twenty-first century needs. They will doubtless long retain their glory, which will draw to them the elite of the elite for the refinement of knowledge. But the educational scale of the future would seem to require solutions in something approaching googol terms.

Still, men are incurably traditional, no doubt because they are irremediably mortal — a circumstance that no amount of material wellbeing is likely to change much. So every revolution prepares a conservatism of new forms. Patterns of convention, symbol, ritual reassert themselves to provide a comfort and a reassuring hand-hold on the slowly sinking ship, which, since each of us always dies, each of us always is. So perhaps, when the great television universities of the future go on the air, beaming their courses from satellite stations orbited in space, students in Katmandu or Cochabamba, before tuning in, may bow three times ceremoniously toward Cambridge (U.K. or Mass.) and the University of California at Los Angeles, though they may no longer know or care just why they make this ritual gesture. Only the oldest old boys may mumble, between their stainless steel teeth, of a legend that, in the centuries BTE (Before Television Education), Oxford, Princeton, Yale, and the like, were names for high places of the mind by which the wonder came.

(back to National Review page)

(back to Articles page)

(back to Home page)

One Response to Foot in the Door

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Archives

Tags

Adolf Berle Alexander Ulanovsky Alger Hiss Arthur Koestler Atlas Shrugged Ayn Rand Benn Steil Cold Friday Cold War Communism Dwight Eisenhower FDR George W. Bush Ghosts on the Roof Harry Dexter White Harry Truman Hiss Case House Un-American Activities Committee HUAC Ignatz Reiss John Loomis Sherman John Maynard Keynes Joseph McCarthy Joseph Stalin Karl Marx Leon Trotsky Max Bedacht Middle East National Review Peter the Great Pumpkin Papers Ralph de Toledano Richard Nixon Ronald Reagan Sputnik TIME magazine Tony Judt Vladimir Lenin Walter Krivitsky Westminster Whittaker Chambers William F. Buckley William F. Buckley Jr. Winston Churchill YaltaArt Resources

- B&W Photos from Farm Security Administration-Office of War Information Collection

- Life of the People: Radical Impulse + Capital and Labor

- Art of Marxism

- Comrades in Art

- Graphic Witness

- Jacob Burck

- Hugo Gellert + Gellert Papers

- William Gropper

- Jan Matulka: Thomas McCormick Gallery + Global Modernist

- Esther Shemitz Chambers

- Armory Show 1913

Pages from old website

Official website of Whittaker Chambers ( >> more )

Spycraft

- China Reporting

- CIA

- CIA – Alger Hiss Case

- Cold War Files

- Cold War Studies (Harvard)

- Comintern Online

- Comintern Online – LOC

- CWIHP – Wilson Center

- David Moore – Critical Thinking and Intelligence Analysis

- DC Writers: WC Home

- Economist – Espionage

- Essays on Espionage

- FBI – Rogue DNS Checker

- House – Hearing 08/25/1948

- House – Hiss Subpoena

- InfoRapid: WC

- Max Bedacht

- New York Times – Espionage

- NSA – FOIA Request

- PBS NOVA – Secrets Lies and Atomic Spies

- Richard Sorge

- Secrecy News

- Sherman Kent – Collected Essays

- Spy Museum – SPY Blog

- Thomas Sakmyster – J Peters

- Top Secret America – Map

- UK National Archives

- Vassiliev Notebooks

- Venona Decrypts

- Washington Decoded

- Washington Post – Espionage

- Zee Maps

Libraries

- American Commissar by Sandor Voros

- American Mercury – John Land

- American Writers Museum

- Archive.org – HUAC

- Archive.org – Lazar home

- Archive.org – Lazar Report

- Archives.org: 1948 – Hearings

- Archives.org: 1950 – Sherman Lieber

- Archives.org: 1951 – Sorge

- Archives.org: Ernie Lazar FOIA

- Archives.org: Ernie Lazar FOIA Collection

- Bio – Bennet Cerf

- Bio – Zara Witkin

- Bloomsburg University: Counterattack

- Bloomsburg University: Radical Publications

- Brooklyn Eagle 1948

- Centre des Archives communistes en Belgique

- CIA FOIA WC

- Daily Worker (various)

- Daily Worker: Marxists.org

- DC – Kudos

- DC – ORCID

- DC – ResearcherID

- DC – ResearchGate

- DC – SCOPUS

- Digital Public Library of America

- Erwin Marquit – Memoir

- FBI

- FBI Vault – WC

- Google: Books – WC

- GPO – WC

- GW – ER Papers: WC

- GWU: Eleanor Roosevelt WC

- Harvard College Writing Center – WC Summary

- Hathi: WC

- IISH: Marx Engels Papers

- ILGWU archives

- Images AP

- Images Corbis

- Images Getty Time Life

- Images LOC

- INKOMKA Comintern Archives

- International Newsletter of Communist Studies (Germany)

- JJC/CUNY – HC

- Labor Archives in the United States and Canada

- Life – WC

- LOC LCCN WC

- NBC Learn K-12: Spy Trials

- New Masses (Archive.org) 1926–1933

- New Masses (Marxists.org) 1926–1933

- New Masses (USussex) 1926–1938

- NSA: FOIA requests

- Ollie Atkins Photos

- Open Library: WC

- People: WC

- Poetry: Defeat in the Village

- PSA Communism

- SLU Law: HCase

- SSRN: Berresford – Hiss Case

- SUFL: Collections

- Tamiment: Collections

- Truman Library – John S. Service

- Truman Library – Oral Histories

- Truman Library – WC

- UCBerk * eBooks

- UCBerk: China – Edgar Snow

- UCBerk: China – Grace Service

- UCBerk: China – Kataoka

- UCBerk: China – Mackinnon

- UCBerk: China – Owen Lattimore

- UCBerk: China – Stross

- UCBerk: France – Revolution

- UCBerk: Russia – Bread 1914-1921

- UCBerk: Russia – Comintern

- UCBerk: US – Conservatism WC

- UCBerk: US – Hollywood Weimar

- UCBerk: US – James Joyce

- UCBerk: US – Lawyers

- UCBerk: US – NY Intellectual

- UCBerk: US – Waterfronts

- UCLA Library Film & TV Archive

- UK National Archives: WC

- UMich: Salant Deception

- UPenn: US – Left Ephemera Collection

- UPitt: US – Harry Gannes

- USDOE

- USDoED

- USDOJ

- USDOS

- Wall St + Bolshevik Revolution – Anthony Sutton

- Wikipedia A-D

- WikiSearch WC

- WordPress themes – Anders Noren

- x FSearch – WC

[…] Foot in the Door […]