- Articles

- Commonweal

- TIME – Reviews

- TIME – Articles

- TIME – Cover Stories

- TIME – Foreign News

- Life Magazine

- Harper’s: A Chain is as Strong as its Most Confused Link

- TIME – Religion

- New York Tribune

- TIME

- National Review

- Soviet Strategy in the Middle East

- The Coming Struggle for Outer Space

- The Left Understands the Left

- To Temporize Is Death

- Big Sister Is Watching You

- Springhead to Springhead

- Some Untimely Jottings

- RIP: Virginia Freedom

- A Reminder

- A Republican Looks At His Vote

- Some Westminster Notes

- Missiles, Brains and Mind

- The Hissiad: A Correction

- Foot in the Door

- Books

- Poetry

- Video

- About

- Disclaimer

- Case

- Articles on the Case

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1948

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1949

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1950

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1951

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1952

- Trial by Typewriter

- I Was the Witness

- The Time News Quiz

- Another Witness

- Question of Security

- Fusilier

- Publican & Pharisee

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Kudos

- Letters – June 16, 1952

- Readable

- Letters – June 23, 1952

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Nominee for Veep

- Recent and Readable

- Recent and Readable

- Democratic Nominee for President

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Fighting Quaker

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Recent & Readable

- Timely Saints

- Nixon on Communism

- People

- Who’s for Whom

- 1952 Bestsellers

- Letters – December 15, 1952

- Year in Books

- Man of Bretton Woods

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1953

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1954

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1955

- Hiss Case Coverage: TIME 1956-1957

- Private

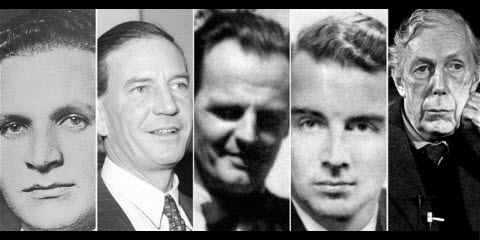

[Arnold Deutsch, Kim Philby, Donald Maclean and Guy Burgess, Anthony Blunt – Daily Telegraph]

The London Review of Books has published this comment on Inigo Thomas‘s piece, “High Priestess of Anti-Communism“:

Mr. Thomas,

The MI5 documents published by the UK’s National Archives last month on Whittaker Chambers/Alger Hiss were indeed of interest.

For me (a grandchild of Whittaker Chambers), it was an earlier document in that collection that caught my attention. It comes from an “R. T. Reed,” dated November 20, 1952, regarding Chambers’s 1952 memoir Witness. Random House had published the book in May 1952. Months ahead of the UK edition published in 1953, Reed’s commentary adds to an impressive list of dispassionate British observations on the Hiss Case.

Reed tones down the American focus on Hiss versus Chambers. He also downplays the Ware Group. Instead, his interest lies in the international character of the Soviet Underground. Thus, Reed mentions Walter Krivitsky early on. (Krivitsky was brief successor to Ignace Reiss, head of the GRU‘s Western European operations.) A footnote mentions “Ulanov,” corrected by pencil as “Ulanovski”: Alexander Ulanovsky was one of Chambers’s first Soviet rezident handlers. Another footnote notes Chambers’s involvement in setting up “an espionage network in England.”

Reed quotes at length a passage from Chambers’s memoir, more completely quoted here:

In a situation with few parallels in history, the agents of a foreign power were in a position to do much more than purloin documents. They were in a position to influence the nation’s foreign policy in the interests of the nation’s chief enemy, and not only on exceptional occasions like Yalta (where Hiss’s role, while presumably important, is still ill-defined) or through the Morgenthau Plan for the destruction of Germany (which is generally credited to [Harry Dexter] White), but in what must have been the staggering sum of day-to-day decisions. The power to influence policy had always been the ultimate purpose of the Communist Party’s infiltration. It was much more dangerous, and, as events have proved, much more difficult to detect, than espionage, which beside it is trivial, though the two go hand in hand. (Witness, p. 472)

Reed underscores: “The power to influence policy had always been the ultimate purpose of the Communist Party’s infiltration.”

He concludes at one point: “In the technical sense, the Ware Group was not primarily an espionage group.” Then, again he quotes Chambers: “The real power of the [Ware] Group lay at much higher levels. It was a power to influence, from the most strategic positions, the policies of the United States Government.” (Witness, p. 343)

“The power to influence” — Reed must have had the Cambridge Five in mind. After all, Donald Maclean and Guy Burgess had disappeared only the summer before (1951). Reed mentions, “The following passages might well have been written about this country bearing in mind our own discoveries and beliefs.” (Another document dated April 7, 1951, records an FBI memo about an informant who claimed that “Mclean was in contact with Alger Hiss” twice in October 1946.)

Reed notes that Witness has “a full index at the end of the book which is very useful.” One document considers who might be a “British Communist” mentioned in Witness. One suspect is a Glaswegian named Tom Bell, another a Mancunian named Jim Crossley (shades of Alger Hiss’s “George Crosley”?).

International connections between the US and UK permeate these documents. They reflect the global spy network. While in service, Chambers knew it as the “Soviet Underground.” After he defected, Krivitsky told him it was the Fourth Department of the Red Army or “GRU” (to use its Soviet acronym). One document talks about Chambers’s official recruiter, Max Bedacht, who ordered him to join the Underground. The same mentions John Loomis Sherman, who trained him in Soviet espionage.

Much seems to have missing in the MI5 documents just published. Did MI5 ¬not investigate? One document dated February 15, 1951, discusses Maxim Lieber, a literary agent who worked with Chambers to set up the “espionage network in England” mentioned earlier. It questions whether Lieber’s relationship to “Budberg” (Moura Budberg) extended to anything beyond literary interests.

Was there no more investigation?

In Witness, Chambers talks a length about a branch of Lieber’s literary agency he was to establish in London. Later, he writes, Sherman was to go to London in Chambers’s stead. (By then posted instead to the Ware Group in Washington.) A document cited above mentions that Hiss knew Mclean. Krivitsky and Reiss helped oversee the setting up of the Cambridge Five.

Are we to believe that MI5 did no more to tie Chambers with the Cambridge Five?

(See original online at London Review of Books)

Tagged with: Alexander Ulanovsky • Alger Hiss • Communism • Donald Maclean • GRU • Guy Burgess • Harry Dexter White • Ignace Reiss • John Loomis Sherman • Max Bedacht • MI5. Maxim Lieber • Moura Budberg • R. T. Reed • Walter Krivitsky • Ware Group • Whittaker Chambers

One Response to MI5 Papers on Hiss-Chambers Case

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Archives

Tags

Adolf Berle Alexander Ulanovsky Alger Hiss Arthur Koestler Atlas Shrugged Ayn Rand Benn Steil Cold Friday Cold War Communism Dwight Eisenhower FDR George W. Bush Ghosts on the Roof Harry Dexter White Harry Truman Hiss Case House Un-American Activities Committee HUAC Ignatz Reiss John Loomis Sherman John Maynard Keynes Joseph McCarthy Joseph Stalin Karl Marx Leon Trotsky Max Bedacht Middle East National Review Peter the Great Pumpkin Papers Ralph de Toledano Richard Nixon Ronald Reagan Sputnik TIME magazine Tony Judt Vladimir Lenin Walter Krivitsky Westminster Whittaker Chambers William F. Buckley William F. Buckley Jr. Winston Churchill YaltaArt Resources

- B&W Photos from Farm Security Administration-Office of War Information Collection

- Life of the People: Radical Impulse + Capital and Labor

- Art of Marxism

- Comrades in Art

- Graphic Witness

- Jacob Burck

- Hugo Gellert + Gellert Papers

- William Gropper

- Jan Matulka: Thomas McCormick Gallery + Global Modernist

- Esther Shemitz Chambers

- Armory Show 1913

Pages from old website

Official website of Whittaker Chambers ( >> more )

Spycraft

- China Reporting

- CIA

- CIA – Alger Hiss Case

- Cold War Files

- Cold War Studies (Harvard)

- Comintern Online

- Comintern Online – LOC

- CWIHP – Wilson Center

- David Moore – Critical Thinking and Intelligence Analysis

- DC Writers: WC Home

- Economist – Espionage

- Essays on Espionage

- FBI – Rogue DNS Checker

- House – Hearing 08/25/1948

- House – Hiss Subpoena

- InfoRapid: WC

- Max Bedacht

- New York Times – Espionage

- NSA – FOIA Request

- PBS NOVA – Secrets Lies and Atomic Spies

- Richard Sorge

- Secrecy News

- Sherman Kent – Collected Essays

- Spy Museum – SPY Blog

- Thomas Sakmyster – J Peters

- Top Secret America – Map

- UK National Archives

- Vassiliev Notebooks

- Venona Decrypts

- Washington Decoded

- Washington Post – Espionage

- Zee Maps

Libraries

- American Commissar by Sandor Voros

- American Mercury – John Land

- American Writers Museum

- Archive.org – HUAC

- Archive.org – Lazar home

- Archive.org – Lazar Report

- Archives.org: 1948 – Hearings

- Archives.org: 1950 – Sherman Lieber

- Archives.org: 1951 – Sorge

- Archives.org: Ernie Lazar FOIA

- Archives.org: Ernie Lazar FOIA Collection

- Bio – Bennet Cerf

- Bio – Zara Witkin

- Bloomsburg University: Counterattack

- Bloomsburg University: Radical Publications

- Brooklyn Eagle 1948

- Centre des Archives communistes en Belgique

- CIA FOIA WC

- Daily Worker (various)

- Daily Worker: Marxists.org

- DC – Kudos

- DC – ORCID

- DC – ResearcherID

- DC – ResearchGate

- DC – SCOPUS

- Digital Public Library of America

- Erwin Marquit – Memoir

- FBI

- FBI Vault – WC

- Google: Books – WC

- GPO – WC

- GW – ER Papers: WC

- GWU: Eleanor Roosevelt WC

- Harvard College Writing Center – WC Summary

- Hathi: WC

- IISH: Marx Engels Papers

- ILGWU archives

- Images AP

- Images Corbis

- Images Getty Time Life

- Images LOC

- INKOMKA Comintern Archives

- International Newsletter of Communist Studies (Germany)

- JJC/CUNY – HC

- Labor Archives in the United States and Canada

- Life – WC

- LOC LCCN WC

- NBC Learn K-12: Spy Trials

- New Masses (Archive.org) 1926–1933

- New Masses (Marxists.org) 1926–1933

- New Masses (USussex) 1926–1938

- NSA: FOIA requests

- Ollie Atkins Photos

- Open Library: WC

- People: WC

- Poetry: Defeat in the Village

- PSA Communism

- SLU Law: HCase

- SSRN: Berresford – Hiss Case

- SUFL: Collections

- Tamiment: Collections

- Truman Library – John S. Service

- Truman Library – Oral Histories

- Truman Library – WC

- UCBerk * eBooks

- UCBerk: China – Edgar Snow

- UCBerk: China – Grace Service

- UCBerk: China – Kataoka

- UCBerk: China – Mackinnon

- UCBerk: China – Owen Lattimore

- UCBerk: China – Stross

- UCBerk: France – Revolution

- UCBerk: Russia – Bread 1914-1921

- UCBerk: Russia – Comintern

- UCBerk: US – Conservatism WC

- UCBerk: US – Hollywood Weimar

- UCBerk: US – James Joyce

- UCBerk: US – Lawyers

- UCBerk: US – NY Intellectual

- UCBerk: US – Waterfronts

- UCLA Library Film & TV Archive

- UK National Archives: WC

- UMich: Salant Deception

- UPenn: US – Left Ephemera Collection

- UPitt: US – Harry Gannes

- USDOE

- USDoED

- USDOJ

- USDOS

- Wall St + Bolshevik Revolution – Anthony Sutton

- Wikipedia A-D

- WikiSearch WC

- WordPress themes – Anders Noren

- x FSearch – WC

Good afternoon, I hope I’m not too late for a response. You have a pic of Arnold Deutsch on your header – I have been chasing him for quite some time, as the linked website shows, and optimistically believe I might have an idea as to where the gentleman ended his days, right in the middle of the South Australian atomic weapons and bombs development program.

Everything seems to fall into context, it’s as good as fiction.